Decolonisation and human rights are inextricably linked. Colonial powers have often imposed systems of power and oppression through force or coercion. Decolonisation is the process of dismantling these systems. This process is essential for advancing and safeguarding human rights in colonised and postcolonial territories. Human rights have served as empowering tools during the decolonisation process. They help to end the oppressive and exploitative systems of colonialism that violate the human rights of colonised peoples. As such, decolonisation is based on the principles of human rights, the recognition of the rights of colonised peoples, and the right to development.

However, the process of decolonisation is complex and multifaceted and involves both political and social change. The process is often misunderstood or conflated with other social justice movements such as diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Picture: Shoukat Lohar/Daily Times

Modern colonialism

The “Age of Exploration” in the 15th century marked the beginning of modern colonialism, which lasted until the 20th century. Colonial powers justified their conquests by claiming that they had a legal and religious obligation to take over indigenous peoples’ lands and cultures. Some of the most dominant colonial empires in the world were the Portuguese, Spanish and Ottoman empires (Watts, 2009). In addition to conquering and settling in territories in the Americas, Africa, the Middle East and Asia, they also engaged in intense competition as they sought to claim new lands and expand their empires. The competition between the two powers helped to drive the expansion of European colonialism around the world (Ahmed, 2020). The exploitation of the colonised peoples and their resources for the benefit of the colonising powers characterised this period of colonialism.

the Beginning Of Decolonisation

The wave of decolonisation that characterised the latter half of the 20th century was hailed as a great liberating revolution (Quintero, 2012). However, the decolonisation process was often long and challenging, marked by resistance and struggle from colonised peoples and violence and conflict. Several factors influenced the decolonisation process:

- Major colonial powers were left depleted and in ruins at the end of World War II.

- The economic costs of maintaining colonies and the desire for greater economic development, combined with the changing political and economic landscape, led many colonising powers to re-evaluate their colonial policies (Kitchen, 2014).

- The rise of nationalist movements in many colonised countries.

- The rise of the Cold War afterwards also led to a shift in the global balance of power. Major superpowers such as the United States of America and the Soviet Union supported the decolonisation process in 1945. In the same year, the Charter of the United Nations (UN) was born.

The links between colonialism and human rights

The 20th-century decolonisation wave forged the modern human rights framework. It states that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”. Thus, decolonisation is closely tied to the promotion and protection of human rights, which are the fundamental rights and freedoms that all people are entitled to by virtue of their humanity. The essence of human rights and decolonisation share a common characteristic: the struggle for liberty against the abuse of authority. Although decolonisation has sometimes resulted in human rights violations, it can also be a powerful force for advancing and protecting human rights.

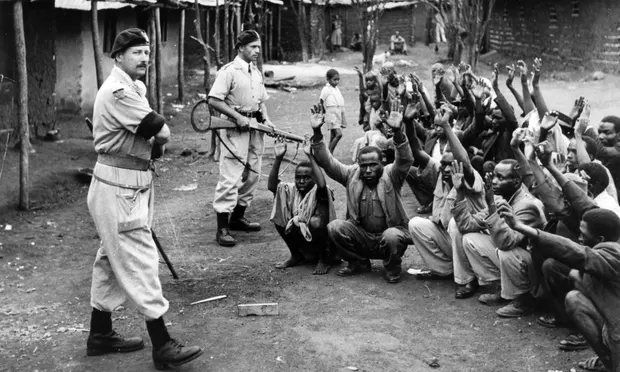

Colonising powers have often sought to maintain their control and resist change, leading to unjust policies. As such, colonised populations have lost their lands, resources, cultural or religious identities, and even their lives. Examples of brutal policies and human rights atrocities include slavery (e.g. British-controlled West Indies), apartheid (e.g. South Africa), and mass murder (e.g. the Incas of Peru, the Aborigines of Australia, and the Hungarians after the 1956 uprising)(Marker, 2003). Consequently, decolonisation has led to many important advances in human rights (Eckel, 2014). Marginalised groups have gained greater control over their own lives and destinies and have been able to assert their rights and demand justice and equality.

Granting independence to colonies

Approximately 750 million people, or nearly a third of the world’s population, lived in territories controlled by colonial powers. After the establishment of the UN in 1945, 80 former colonies gained their independence. The emergence of nationalist movements among the colonised led people to assert their right to self-determination and demand an end to foreign domination. This movement gained a strong legal basis in 1966 with the enforcement of legally binding instruments upholding the right to self-determination (Shrinkhal, 2021).

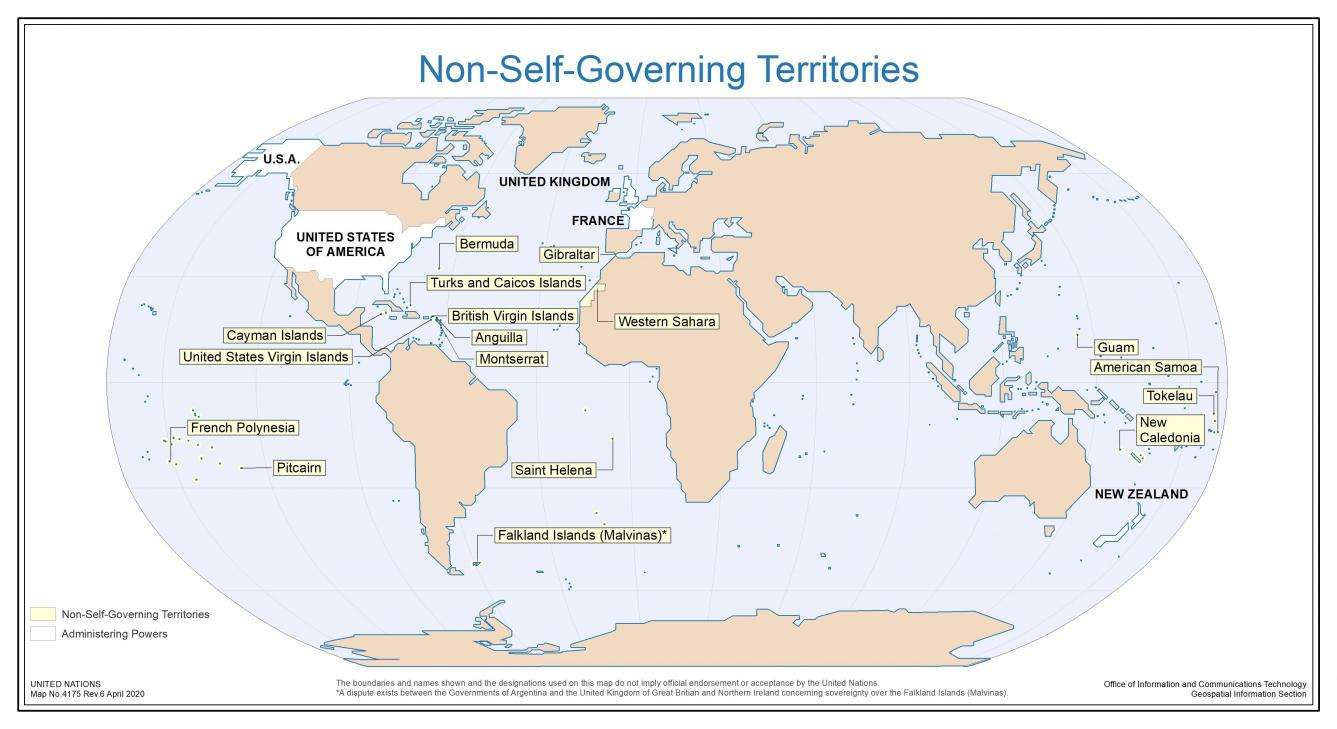

Image: United Nations

However, 17 Non-Self-Governing Territories (NSGTs) still exist, and nearly two million people live in them. The majority are islands in the Caribbean and the Pacific. The UN refers to NSGTs as “territories whose people have not yet attained a full measure of self-government.”. Thus indicating that the decolonisation process is ongoing.

Successfully ending this decolonisation process cannot simply involve removing the 17 territories from the list of NSGTs. It must involve the actual achievement of full self-government (Quintero, 2012). Completing this task will require ongoing dialogue among the administering powers, the 29 different nations that make up the UN Special Committee on Decolonisation, and the NSGTs. They would promote the well-being of the inhabitants of the territories and the development of their self-government.

The effects of colonisation on human rights in the present day

It is difficult to make general claims about the impact of colonialism on the colonised and the development of the colonies because there is no clear counterfactual to compare it to (Heldring & Robinson, 2012). However, this does not negate the reality that colonisation had devastating repercussions on society and minorities. Many post-colonial and post-Soviet governments adopted oppressive colonial practices and policies as a means to preserve their dominant status. Colonial legacies are still visible today because sovereignty did not bring freedom from imperialist influences. Even after many countries gained independence, the effects of colonisation are still present.

Community displacement

Colonial powers erected artificial borders across regions such as the Middle East, North Africa (MENA) and South Asia in their pursuit of dominance and resources (Papaioannou & Michalopoulos, 2012). Arbitrary borders were often drawn with little regard for the history, culture, or geography of the area. As a result, they frequently cut across existing communities and territories, causing conflict and instability (Wantchékon & García-Ponce, 2014). For instance, the ongoing cross-border military standoff in the Kashmir region is a result of the partition of British India. The British withdrew from the Indian subcontinent in 1947, dividing it into two new countries: India and Pakistan. The haphazardly drawn border split communities and forced them to choose which country they belonged to causing widespread bloodshed and displacement.

Ethnic Rivalry

Colonisers have often used the tactic of “divide and rule” to maintain control over their colonies. They’ve also favoured one group over others, creating divisions among various ethnic and religious groups and preventing them from uniting against their oppressors (Marker, 2003). This practice also led to the formation of multi-ethnic and/or multi-confessional entities within newly constituted borders.

One such example is the Hutus and the Tutsis, two different tribes that lived in Rwanda and Burundi. Belgian colonisers racialized both tribes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They favoured the Tutsis over the Hutus, seeing them as more “civilised” and better suited to rule. As a result, the Tutsis were given more power and privilege, while the Hutus were often marginalised and oppressed. After Rwanda and Burundi gained independence from Belgium, the tensions between the Hutus and Tutsis continued to escalate. Eventually laying the groundwork for the 1994 genocide that killed nearly one million ethnic Tutsi and moderate Hutus.

Racism and discrimination

Racism persists after decolonisation due to the legacy of colonialism and other factors such as economic inequality and discrimination. The #BlackLivesMatter movement is a global movement that emerged in response to the ongoing discrimination and violence against Black people. Similarly, the #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall movements in South Africa were inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement. These movements focused on issues related to the high cost of education and the legacy of colonialism in South Africa (Mavunga, 2019).

Unequal distribution of resources

Colonisers often favoured one group over another, resulting in certain groups or tribes receiving higher status and better treatment. This preferential treatment also gave certain groups access to more opportunities and resources, contributing to ongoing inequality and discrimination (Marker, 2003). This legacy of unequal treatment and resource distribution has had negative effects on post-colonial societies, even after decolonisation. South Africa is one such example. Even after the end of apartheid in 1994, the legacy of centuries of colonialism and segregation continues to disproportionately impact Black South Africans. Challenges faced include higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and other social and economic issues (Sguazzin, 2021).

In contrast, European colonisers claimed to bring civilization and economic development to colonised lands. However, this economic development focused on constructing infrastructure to acquire and extract resources. They also promoted literacy, the adoption of Western human rights standards, and the establishment of democratic institutions and governance systems.

Image: Getty Images

Economic inequality

Colonialism is a major factor behind today’s large differences in economic inequality among countries. Some colonies, such as South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Brunei, have experienced rapid economic growth and become prosperous. While others, like Liberia and Haiti, remain among the poorest countries in the world (Jansen et al., 2017). Additionally, the various colonising powers did not always transplant the same institutions. The unique circumstances of a colony often influenced the institutions established there. For example, the presence of large, fertile tracts of land suitable for agriculture shaped the British colonies in North America. Comparativey, the Spanish colonies in Latin America often focused on the extraction of natural resources, such as gold and silver.

Rights denied to minorities

Even after independence, certain groups, notably minorities and indigenous peoples, continue to face discrimination and have their rights denied to traditional lands, resources, and cultural languages, just as they were during colonial occupation. For example, former Sri Lankan Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake’s first move soon after Sri Lanka gained independence from the British in 1948 was the disenfranchisement of the Up-Country Tamils (Kadirgamar, 2017). The British plantation owners brought them to the Sri Lankan plantations from India as estate workers. Despite their significant contribution to the national economy, their citizenship was revoked and they were labelled as “temporary immigrants.” Despite the Sri Lankan government’s efforts to grant them citizenship rights in the 1980s, they still lack access to basic necessities like nutritious food, a good education, or adequate health care.

Lack of governmental structures, skills and experience

After decades of foreign domination, newly independent governments often lacked the structures, governance abilities, and governing experience needed to effectively manage their new sovereign nations. In most cases, the transition from a colonial province to an independent state was violent and complex (Marker, 2003). Independence also often brought a great deal of domestic political turmoil. Because colonial rulers limited the influence of colonised peoples on the way their own countries were run, the citizens of newly independent nations had inadequate knowledge of how to keep the nation-state running (Campbell et al, 2010).

When Europeans left Africa, some African nations did not have the institutions necessary to thrive in the post-war industrial world (Wantchékon & García-Ponce, 2014). Most European rulers did not control their African possessions directly, but rather through local rulers acting as proxies. The departure of the Europeans rendered native rulers and elite classes illegitimate, leaving a need for a new set of rulers with no experience or knowledge of governing. The continent today is beset with violent extremism and civil unrest.

Existing colonial laws

It’s common for modern legal systems to be based on or influenced by colonial laws, either directly or through their incorporation into later legal codes. Many countries that were once colonies of the British Empire, such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and India, have legal systems that are based on English common law. Colonial domination also strongly influenced how people think about class, culture, gender, and sexuality. For instance, the colonial-era “anti-sodomy” legislation that criminalised homosexuality in many nations around the world has never been repealed. Homosexuality is illegal in around 69 countries, nearly two-thirds of which were under British control at one point in time.

Queen Elizabeth II inspects men of the newly-renamed Queen’s Own Nigeria Regiment, Royal West African Frontier Force, during her Commonwealth Tour in Nigeria, in February 1956.

Image: Getty Images

Decolonisation is a battle on its own

Overall, the relationship between decolonisation and human rights is complex and dynamic. In the past, we saw the abuse of power through colonial domination. Now, the human instinct to dominate takes different forms. The same dynamic holds true: those in power carry out abuses for which the rest pay.

The effects of colonialism should not be overlooked or dismissed as insignificant. They continue to impact how nations conduct their domestic and international policies in the present day. Therefore, the fight to decolonise human rights is ongoing. To remain loyal to the nature of human rights, we must acknowledge the past and take into account its continuing effects on post-colonial societies. It is important to examine the actions of colonisers and the colonised to avoid similar consequences in the future. The international community, the public, and the people of NSGTs must be reminded that the UN agenda on decolonisation is vital for protecting fundamental human rights, promoting democratic governance, and upholding an international order based on sovereignty and the equality of states.

The 21st century and the nearly 2 million people still living under colonial rule deserve better.

To learn more about how The THRIVE Project is researching, educating and advocating for a future beyond sustainability, visit our website. You can follow our informative blog and podcast series and find out about our regular live as well as our regular live webinars featuring expert guests in the field. Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates.