What is ‘Caring for Country’?

In Australia, indigenous custodians have managed the land for at least 65 000 years. First Nations people are the oldest living culture in our world.

Long before colonisation, they practiced Indigenous Land Management (ILM). Indigenous custodians developed and honed various land management practices known as caring for country. The result is a deep knowledge of the intricacies of the Australian landscape and the conditions under which it flourishes.

First Nations people regard the land as a person, a living entity. ‘Country’ relates to plants, animals, water, soil, culture, and more. However, beyond its physical features, ‘Country’ refers to an inextricable link between the land and its people.

This connection is based on an obligation to care for Country as custodians and stewards of the land. Therefore, for First Nations people, ‘caring for Country‘ represents those activities that protect, maintain, and heal the land and sustain their culture. Thus, the saying, ‘healthy country, healthy people’ relates to their role as custodians. The people’s well-being is directly related to how well they look after the land.

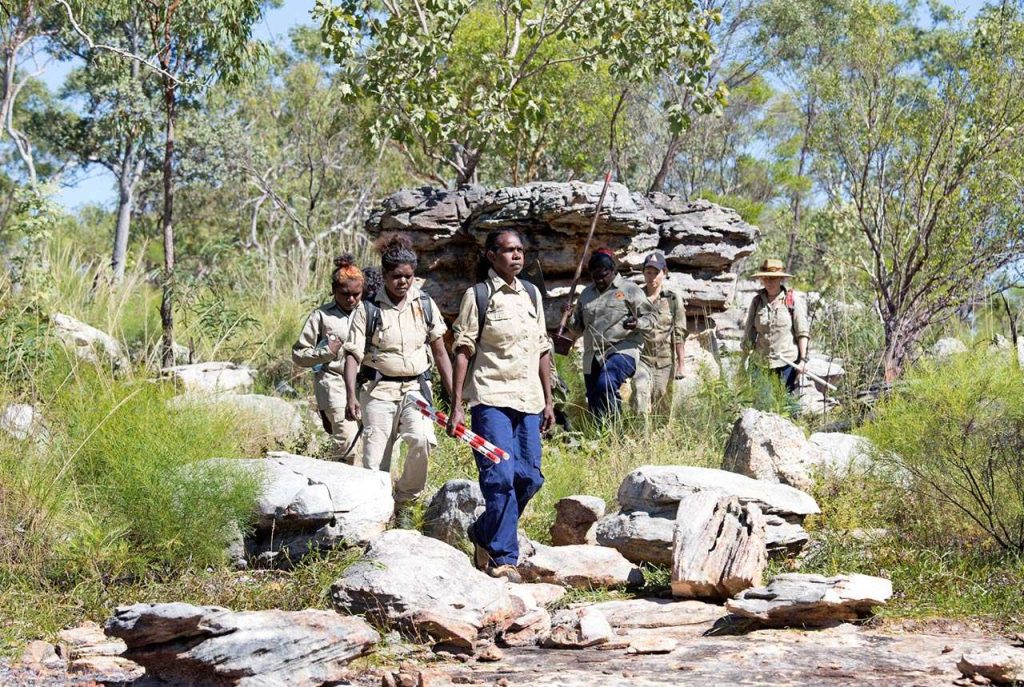

The maintenance of ILM is important for sustainability. It helps us recognise unsustainable practices and reduce harm caused to the environment. Indigenous custodians pass on ILM activities with knowledge sharing across generations. They include fire management, weed, and pest control, water quality testing, and more.

“Indigenous people are best placed to give advice because having that value of Country and water and the knowledge that comes with that – and the laws that protect that – is key to the way we fix the problem.”

– Brad Moggridge, lead author of the Our Knowledge, Our Way guidelines

The Importance of Land Management to Indigenous Custodians

Therefore, the value of ILM lies in the connection between First Nations people and the land. ILM represents an integral part of who they are as custodians. This is due to the close relationship between their knowledge of the land and First Nations culture. By contrast, non-indigenous culture tends to have a one-way perception of the land. This perspective views the land as a separate entity from its inhabitants.

However, First Nations peoples’ spiritual connection to the land goes even deeper than that. Thus, when the Country is ‘sick’, it impacts upon its people. They must practice ILM in order to rejuvenate it.

Furthermore, proper ILM is enabled by the recognition of land rights. This bestows access indigenous custodians and promotes connection and healing. The Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NT) 1976 (Cwlth) and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1986 were created to recognise the importance of traditional land to First Nations people.

Indigenous Land Management (ILM) Practices

ILM practices are unique and peculiar to a diversity of indigenous custodians across Australia. Each possess localised techniques and knowledge specific to their lands. Interaction and adaptation to circumstances has helped to build and improve this knowledge over time.

Some of these methods include:

- Fire management

- Feral animal and weed control

- Monitoring threatened species

- Water conservation

- Dust mitigation

- Harvesting plant foods and medicines for commercial purposes

- Documentation and transfer of traditional knowledge

- Carbon sequestration

- Cultural resource management through expressions of art

Fire Management in the past and present

First Nations people understand fire management in a holistic way, as noted by the respected fire ecologist, Dean Yibarbuk. Traditional Knowledge (TK) is used to conduct burning with low-intensity fires lit in small areas by foot.

This practice traditionally occurs during the early dry season using fire sticks. It is known as cool burning or ‘cultural burning’, and differs from prescribed burning. The participation of First Nations people with their local knowledge makes it a safe and sustainable way to manage the fire season.

Today, projects sometimes combine TK and ‘Western’ science to:

- Mitigate the effects of bushfires by reducing its fuel loads

- Enhance biodiversity

- Strengthen the transmission of traditional knowledge among First Nations people.

Indigenous Savanna burning project

Establishing effective collaboration aids the success of adaptive fire management. Collaborative projects are undertaken by Indigenous rangers, park rangers, pastoralists, and private conservation groups. These partnerships allow for the integration of both new and traditional practices. For instance, burning has been managed through helicopters, remote sensing, and satellite imagery. Nevertheless, they still practice on-the-ground burning which protects sensitive vegetation and cultural sites.

The Benefits of Indigenous Sustainability

The primary benefits of Indigenous sustainability include:

1. Health and Wellbeing

The strengthening of First Nations people’s involvement with ILM can enhance their sense of control and autonomy. This mediates the impacts of sustained stress that could lead to chronic disease or illness.

A study conducted in a remote community in the Northern Territory also highlighted the correlation between Indigenous sustainability and health. It showed that engaging with the land helped save $268,000 p.a. in primary healthcare due to the reduction in health risks.

ILM also contributes to their improved well-being. It allows for the strengthening of their identity, empowerment of their sense of self, and engagement in enjoyable physical activity.

2. Environmental Benefits

The various practices are impactful in reducing climate change, protecting endangered species, and nourishing the biodiversity of the land.

Cultural burning also has a significant influence on reducing the severity and extent of bushfires. Additionally, access to land and effective partnerships allow for greater knowledge of the land. The Dugong and Marine Turtle project reflects this benefit. Through this work, participants were able to increase their knowledge of turtles and dugongs. As a result, they reduced feral animals and marine debris throughout Kimberley to Cape York.

3. Social and Cultural Benefits

The increased ability of Indigenous people to govern their land emphasises the cultural benefits gained from ILM. Local governance creates spaces for First Nations people to discuss ‘caring for Country’ and preserve the transfer of knowledge. These discussions could also help others within their communities. For instance, programs were created to provide greater support for women’s participation in ILM. This helps to ensure the conservation of nature and their cultural heritage.

4. Economic Benefits

The economic benefits produced by ILM encompass employment opportunities and addressing their economic disadvantages. These opportunities could include eco-tourism, carbon sequestration, and art-related businesses. For instance, Waanyi-Garawa rangers in Borroloola are creating a carbon project which is predicted to abate 10,000 – 20,000 tonnes of CO2-e per annum. As well as, generate benefits between $100,000-$200,000 per annum.

Barriers for First Nations People

One major barrier is the limited respect and continuation of support for Indigenous practices. This persists due to the power imbalances between western and Indigenous knowledge. This is conveyed when First Nations people simply play the role of “consultants”. The lack of respect is also conveyed when Indigenous knowledge is commercially exploited. Therefore, depriving them of the benefits of their own practices.

Additionally, the lack of support is based on the lack of security in their funding. This is a result of the unstable nature of policies regarding Indigenous matters. Therefore, this produces short-term funding opportunities that do not ensure their full access to resources and wages. Further implications have trickled into their capacity to recruit staff and deliver effective outcomes.

Policies also affect the barriers to economic opportunities in carbon projects. The Native Title Act and Indigenous Land Use Agreement recognise First Nations people’s rights and interests with the land. However, it limits their economic property rights and capacity to develop land for their local community.

How to Support Indigenous Land management

As a result, self-determination would ideally develop when First Nations people have an increased engagement with stewardship activities. This would include the acknowledgment of these rights in all levels of interaction and ensuring that they have dominant positions within these projects.

This allows for them the dignity of maintaining their culture passed down from their ancestors. For that reason, it would reassert their ability to practice their cultural obligations and ensure the good health and well-being of their community.

Fostering Opportunities for Indigenous Custodians

Increased involvement of First Nations people in ILM can be further developed through:

- Long-term relationships of respect, trust, and transparency.

- Creating effective partnerships through equitable two-way knowledge systems that support Indigenous innovation.

- Empowering Indigenous Australian women through more employment opportunities in ranger programs. This could be achieved by providing flexible working arrangements and creating women’s ranger programs.

- Increased and continuous funding for Indigenous-specific government programs

- Providing modern resources, such as multimedia tools to support the transmission of traditional knowledge.

However, we must acknowledge the exciting changes that are beginning to occur for ILM and closing the gap. This is reflected in the Labor government’s claims to implement the Uluru Statement in full.

Nevertheless, it is important to ensure that these policies are fully implemented and protected. In practice, this would involve the formal recognition of Caring for Country as a key method toward addressing climate change.

Ultimately, traditional knowledge promises many solutions for our current sustainability and environmental challenges. Australia can make significant progress to enact these sustainable practices and healing for First Nations people. However, it would require respectful and continuous partnerships that appreciate each other’s values.

The Thrive Project promotes solutions that are transdisciplinary and value-based. These values are important alongside other issues that address closing the gap for First Nations people. Join the Thrive Project as a volunteer and help us to educate and advocate for ‘thrivable’ solutions.