The basis of the safeguarding of human rights in developed countries has its roots in the same philosophies that underpin democracy itself. The frameworks of legislative, executive, and judicial power are based upon the ideals embedded in these philosophies, as are the systems that ensure individual protection and institutional integrity. Concepts such as ‘Habeas Corpus’ and ‘Rule of Law’ date back to 17th century England, from which ‘natural justice’ or ‘natural law’ was formed. As a bedrock to a properly democratic judiciary, said concepts focused on ethical and moral concerns, and in part, specify the right to be heard, including an impartial jury. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (as introduced in the 20th century) also added to this foundation. What is the role of the media in safeguarding these principles?

There are other influences that potentially threaten these safeguards in many countries, requiring some of the most innate judicial and democratic protections to circumvent this influence. These bedrock ideals are coming under threat due in no small part to the role that the media is now playing in modern societies. Now more than ever, the role of the media in society should be questioned.

One illuminating example is the impact of social media as well as traditional media on family/civil and criminal court cases (Browning, 2021), (Garfield-Tenzer, 2019). Live coverage of trials and judicial processes by media companies and social media users have been increasingly intrusive in the digital age. The impact on human rights and the legal process is being felt at every level of our institutions, even in the political sphere. What are the benefits versus the limitations of this new transparency? Is it strengthening or weakening our institutions on matters of law?

‘Trial by Media’

Technological innovation has allowed live coverage of and exposure to personal and humanitarian crises and documented war crimes. It has also provided real-time evidence of crimes and created vast, accessible platforms for campaigns, and action for peace around the world.

However, the flip side of this is that not all social media campaigns are about nonviolence (or are apolitical). Alongside campaigns for peace, there are also campaigns with partisan interests (Boulianne, 2016), ‘social agendas’ and warring parties. These are cases in which social media becomes a battlefield between differing social agendas. The online world creates ‘echo chambers’ (Boulianne, 2016). ‘Echo chambers’ are separated spaces in which ‘one pre-existent view is corroborated by likeminded individuals within established online groups’ (Boulianne, 2016). They also create such a bias that it becomes all too easy to dismiss counterfactual evidence. Many times even scientific evidence ends up dismissed or misrepresented to suit a particular agenda.

Social media has also been weaponised by interest groups in order to spread misinformation (Alcott et al, 2019). These groups promote hate speech toward minorities and sometimes incite violence (Mutahi, et al, 2017). Some groups also attempt to influence policy (Alcott et al, 2019). The weaponization of online content becomes most concerning when misinformation incites violence or hysteria. This can influence policy and legislation (Lynch, et al, 2016), or judicial processes, particularly within criminal cases (Schulz, 2012).

The implications for judicial processes are severe. When cases of defamation and criminal law are saturated by media exposure, this undermines the integrity of legal institutions (Bagaric, 2010). This has shifted the needle to a point whereby Natural Law, Due Process, and human rights are threatened. Due to social media, the undermining of institutional integrity has become apparent (Schulz, 2012).

This is apparent in numerous renown public court cases. The Heard vs Depp defamation trial is one such example. Cases involving serious allegations of murder and sexual assault can become distorted. In less public cases, the intrusion of the media can have an undermining impact on legal processes (Garfield-Tenzer, 2019). In Family Law, online content is used as a means for parties to vent online. Online content can be selectively used in cases that can have a damaging impact on institutional integrity (Wilton, 2012). However, in criminal court cases, the very heart of judicial integrity is threatened. Social media content influences the impartiality of the jury, making a fair trial very difficult (St Eve, et al, 2013).

Media And Justice: Legal Transparency Or Failure Of Law?

Legal transparency is a benchmark of democratic processes and institutional integrity. So too are impartiality and natural law. These principles sometimes come into conflict thanks to the role of the media (Bagaric, 2010). As part of adherence to judicial integrity, early constitutional standards influenced much of the world’s judicial processes (Shauer, 1976). Sometimes legal transparency compromises judicial integrity. This often occurs when the trials are exposed and commentated on social media. In these cases jurors can be made defunct or compromised. Sometimes even judges are swayed (Browning, 2021). In these cases, judicial integrity is likely compromised (Garfield-Tenzer, 2019).

We must acknowledge the impact of social media on judicial processes in order to restore its integrity (Garfield-Tenzer, 2019). The ways that traditional media are regulated may provide a good model (Wolper, 2011). Where no such effort to mitigate this impact is made, there is a failure of law (Garfield-Tenzer 2019). In some instances (for example, in the United States), constitutional rights are breached (Garfield-Tenzer 2019).

Hasn’t it Always Been the Role of the Media to Question Facts?

The ostensible role media plays in society can be dated back to the printing press in the 16th century. Coined as the ‘fourth estate’ in 1787 by British parliamentarian Edmund Burke, the media acts, or is supposed to act, as one of society’s checks and balances of other institutions of power (Gentzkow, et al, 2006). It should, therefore, (in adherence to its traditional role of scrutinising institutions of power to ensure procedural fairness), question, critique and attempt to uncover facts in order to assist assurance of institutional integrity.

When it comes to its own influence on politics (or judicial proceedings), the media often compromises the integrity of other institutions (Schulz, 2012). Many people approach the media with caution and scrutiny. The potential for propagandising to the detriment of fact never fully disappears (Bernays, 1947). Edward Bernays’ writing on the influence of media propaganda during the lead-up to World War One is a powerful reminder of what can go wrong.

The attempt to sway public opinion in favour of the war (due to mass media saturation) was successful (Bernays, 1947). This demonstrates that media dissemination is not always for the public good (or driven by fact-checking). In today’s world the situation has worsened, because social media itself has no system of checks and balances for its own content (Boulianne, 2016).

The History of Media and Justice

Media has always had a history that is entangled with the need to ensure checks and balances. The need to protect democracy, human rights and procedural fairness in justice systems is always central. In the contemporary world, media can prejudice justice systems. This was clearly the case concerning the story of ‘modern-day lynchings’ in India (Vasudeva, 2019). These acts were incited through ‘fake sensationalist social media’ (Vasudeva, 2019).

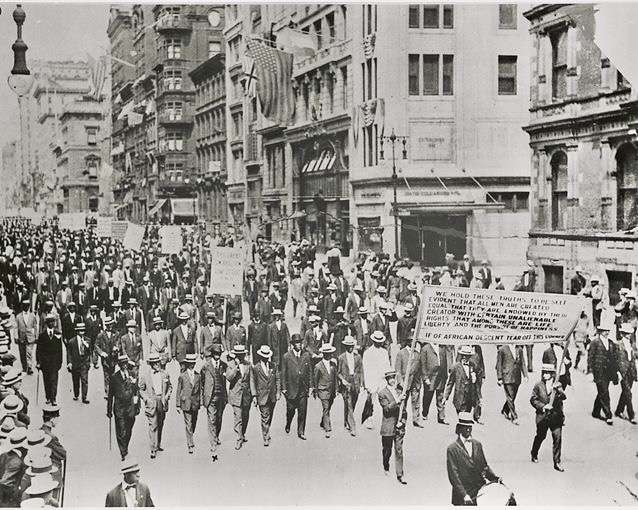

Increasingly, the media is inciting mob rule that is overturning legal procedures and protections. Let us not forget that in the US, print media played a role in justifying the lynching of African Americans. All that was needed was a criminal accusation. This occurred repeatedly up until as late as the 1930s (Weaver, 2019). During this period, the media incited mobs which resulted in extreme human rights abuses, torture and terrorism (Weaver, 2019). Interestingly, other news sources condemned these same acts as ‘undermining the tenets of democracy and human rights’ (Weaver, 2019). There is a concerning symmetry between the role of the media in the past and in today’s world.

The media’s influence can be destructive or constructive. Instead of undermining our common principles, the media should play a part in our system of checks and balances.

Truth and Opinion: Where are the Facts?

Oftentimes opinions outweigh facts. This is particularly evident where “echo chambers” exist (Boulianne, 2016). This can sometimes spill-over and influence policy and law-making (Alcott, 2019). Policy and law-making should be based in fact, rather than swayed by the influence of mobs who happen to share opinions with no factual basis.

Many such mob protests are “informed mostly by predisposed opinion and a lack of any checks and balances or integrity” (Boulianne, 2016). Active community engagement adheres to the general role of the fourth estate. However, in terms of checks and balances as well as participatory democracy, the ability for opinion to usurp fact remains an issue for public dissemination of knowledge and institutional integrity.

What About Media and the Climate Crisis?

The media must also play a role in mitigating the current and future humanitarian crisis we face. Concerning our climate and environmental protection, social sustainability is another area of significance. Social media in particular has allowed worldwide movements to highlight climate issues. The role of traditional media in this regard is also crucial. It is important that we democratically consider what to do (Samantray, et al, 2019).

The tactics of some environmental groups are perceived very negatively when shown in traditional media. These groups are often shut down and shunned. However, many others are also given platforms. Information concerning the environment must be appraised and given proper exposure. When outrage and interest dominate online conversations, the opportunity for important issues to gain publicity is undeniable (Samantray, et al, 2019). The politicised nature of social media undermines this potential to a great extent. When scientific fact is undermined (Fischer, 2019), so to are our chances of talking reasonably. However, the potential for media to create productive discussion around the climate is undeniable.

Conclusion:

The media must play a role in protecting our principles and keeping our institutions strong and in check. This is especially the case in regards to judicial domains, which are especially threatened by modern media. By aiding in the preservation of the democratic integrity and independence of our institutions, the media could ensure the safeguarding of human rights and natural law. The media must also act in a way that counters sensationalism and supports factual reporting. We must recognise the complex history of the media to learn the lessons of the past. Mitigating the climate crisis will require integrity and reasoned discussion. The media has a vital role to play in preparing society for the changes that must come.

THRIVE is interested in issues fundamental to the integrity of our society. Apart from sustainability, this also means examining issues related to the judicial process and human rights. Safeguarding human well-being in all domains is paramount to THRIVE’s mission.

To learn more about how The THRIVE Project is researching, educating and advocating for a future beyond sustainability, visit our website. You can follow our informative blog and podcast series, as well as find out about our regular live webinars featuring expert guests in the field. Sign up for our newsletter for regular updates.