The rate of global population growth has consequences for the planet’s resources. Food, water, shelter, space, energy, clothing, and other things become increasingly scarce as resources are depleted. Producing enough to feed, clean, shelter and clothe the population becomes a significant problem.

The lives of our children will be defined by how quickly we can learn to mitigate climate change. However, much will depend on how we manage our existing resources for future generations.

The ‘Anti-natalists’ are bringing the issue of overpopulation to the environmental debate. Antinatalists advocate for people to have fewer, or no children. They believe that refraining from procreation is the most effective means to minimise environmental destruction.

However, preventing more children from being born to ensure quality of life for those already born creates complex ethical questions. Do the antinatalists have it right?

Antinatalists and the Rate of Population Growth

There are a number of strong philanthropic arguments for antinatalism, including the Asymmetry argument. This says that, when an individual’s life creates even the slightest harm, it is wrong to bring it into existence. It’s credited to the South African philosopher, David Benatar. Benatar is considered the most influential contemporary proponent of antinatalism. He’s also perhaps the world’s most pessimistic philosopher.

Other arguments for Antinatalism include:

- The Deluded Gladness argument (Benatar). This states that, while typical life assessments are often quite positive, they are almost always mistaken in their conclusions.

- The Hypothetical Consent argument. Essentially, procreation imposes unjustifiable harm to an individual for which they did not consent.

- The No Victim argument by Gerald Harrison. To coherently posit

the existence of moral duties means there must be a possible victim.

Ouroboros, the snake devouring its own tail (above), represents the the eternal cycle of destruction and rebirth. The image of Ouroboros being cut is a popular antinatalist symbol. It represents putting an end to the ‘cycle of suffering’.

In Benatar’s book, Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming to Existence (2006), he quotes the Greek tragedian Sophocles: “Never to have been born is best / But if we must see the light, the next best / Is quickly returning whence we came”.

He also quotes Ecclesiastes: “So I have praised the dead that are already dead more than the living that are yet alive; but better than both of them is he who has not yet been, who has not seen the evil work that is done under the sun”.

These quotes suggest antinatalism may have been around for a long time in some form or other.

The Ethical Aspect

The ethical position of antinatalism is that procreation is wrong. This is due to the fact that life’s suffering is inevitable. Suffering, they say, inspired our concept of evil. Therefore, the less people there are, the less evil will take place.

In the current historical context, antinatalism and climate activism have become conflated to some extent. Climate activists worry about bringing newborns into a world threatened by disaster, and in this respect they have much in common with the antinatalists.

Climate activists and antinatalists share a pessimism about the current state of the world. Both are concerned with the concept of intergenerational equity. Intergenerational equity proposes that future generations should have the same, if not greater, access to resources than previous generations.

The Actual Rate of Global Population Growth

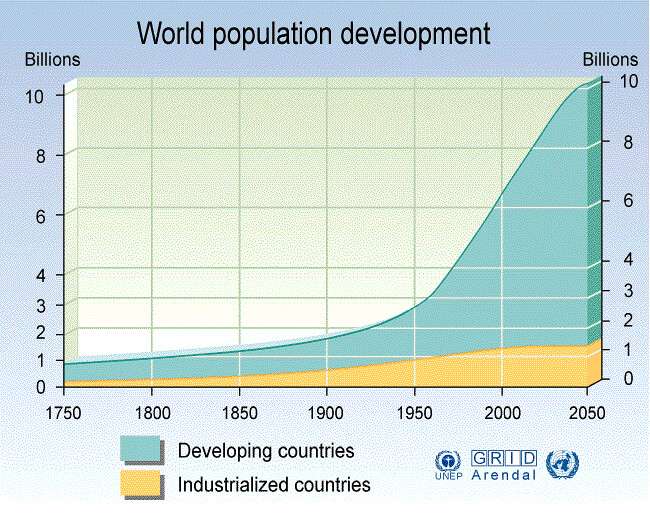

Today, global population growth is steadily rising. Antinatalists argue that humans are a destructive force on the environment, and the problem is getting worse.

The United Nations (UN) population projection for 2050 is 9.8 billion, and by 2100 it will have reached 11.2 billion. This will place an increased demand on resources for each indivisual and every state. The principle of intergenerational equity means that, unless we radically change our lifestyles, quality of life will only decline.

Further, whilst childbirth has halved over the last 50 years, antinatalists believe the current childbirth rate is still way too high.

Why are Birth Rates Declining?

The discovery of antibiotics has had a huge impact on the rate of global population growth. Before antibiotics, rural families in particular used to produce many children. As a result, the family could ensure a good supply of labour and carers for when parents get old. However, after the discovery of antibiotics, life expectancy went up and populations started to rise around the world.

Yet, changes in behaviour did not follow the rise in population. So, the tendency to have large families remained.

Recently, global birth rates have started to decline with the introduction of sex education for rural women and young adults. This accompanies a rise in general education levels and an increase in basic living standards.

Therefore, broad social changes have helped to cause a reduction in global birth rates. There is, however, some concern that this will lead to a ‘population implosion’. One of the most vocal critics of declining birth rates is the entrepreneur, Elon Musk. Musk argues that a population decline will lead to a ‘collapse’ of industry, development, and the world economy.

Birth rates are declining most in the following countries:

- China

- Japan

- Russia

- Netherlands

- Nordic countries (Finland, Norway, and Iceland)

China is perhaps the best-known example of explosive population growth brought to heel by strict controls. After growth became too rapid, the Chinese government imposed a strict one child policy. By contrast, Nordic countries have experienced a declining population over recent decades largely due to higher living standards, education, and more people choosing a career over family.

The Impacts of China’s ‘One Child Policy’

China’s One Child Policy is arguably the largest ‘antinatalist’ experiment in human history. If not in intention, then in its effect. Nevertheless, the outcomes of this policy have been problematic. Firstly, the policy is criticised as a violation of human rights. This is not only because it restricts individual freedom but because it has caused many forced abortions, killings, and sterilisations. Some of the worst consequences of the One Child Policy include:

Infanticide

Many infant Chinese girls were abandoned or killed as a result of the One Child Policy. This was due to a traditional preference for male offspring and the limits imposed by the policy. Boys were considered more economically useful, especially in rural areas. Sex-selective abortions were therefore common. The ‘missing girls‘ phenomenon is where parents deliberately concealed the birth of female children. Sadly, many were killed or given away soon after birth.

Small changes to the One Child Policy were made in response to such horrors. For example, villagers were allowed to have a second child if their firstborn was a girl. This may have helped to reduce infanticide. The practice has, in any case, diminished dramatically in recent decades.

Fines and forced abortions

Parents who had a second child had to pay fines and would lose access to basic services. Denial of access to social services like health care and education for a second child has imposed an enormous burden on many families. This would have certainly contributed to forced abortions.

Population imbalance

China’s fertility rate and birth rate decreased after 1980. According to the Chinese government, the One Child Policy prevented around 400 million births. However, the numbers of missing girls have caused researchers to contest this figure. Nevertheless, the combination of lower birth rates and infanticide reshaped China’s population drastically. There were 120 males for every 100 females in the 2000s. It is now an increasingly elderly and male-dominated population. A shortage in the availability of ‘brides’ for Chinese men is thought to have been caused by this gender imbalance.

Economic constraints

The rapidly ageing population and shrinking workforce led China to ease its One Child Policy in January, 2016. The government was concerned that strict population controls were undermining economic growth. Nevertheless, the country’s 2020 census confirmed that 12 million babies were born in that year, which was a reduction from 14.65 million in 2019. So, in May 2021, Beijing announced it would allow each couple to now have three children. However, perhaps due to China’s high cost of living, the birth rate declined for a fifth consecutive year to a new record low in 2021.

The outcomes of China’s one-child policy give caution to the arguments put forward by the antinatalist movement. Any kind of population policy proposed today must consider the risks of population imbalance. Equally, it must take into account gender equality and reproductive rights.

are People Choosing not to have Children?

In most developed countries, fertility declined to a level below population replacement by 2015-2020. Even without strict population controls, the rate of global population growth is declining. The reason couples are choosing to go ‘child-free’ are manifold:

The Cost of Living and Economic Crisis

As the cost of rent, housing, medical care and costs of living in general increase, many millennials and Gen Z worry that they won’t be able to afford the life they feel their kids deserve. Birth rates also tend to dip after economic crises as couples delay having babies because of uncertainty regarding jobs and income.

Contraceptives, New Innovations and Freedom of Choice

According to a study by the NHS, approximately 1 in 5 women are childless at midlife. Of those, 10% have made the decision not to have children. 80% are childless due to not having found a suitable partner, their partner not wanting to have children, or because they were caring for a relative. With new technology and increasing access to contraception, women are more empowered to delay or limit childbirth. Moreover, couples are more inclined to be child free as it gives them more decision-making power in their lives.

The State of the Planet

Ongoing global issues such as war, pandemics (i.e. COVID-19), natural disaster and climate change is a significant deterrent for some potential parents. Others are putting off having children because of concerns about the environment.

Are Environmental Concerns a Valid Reason?

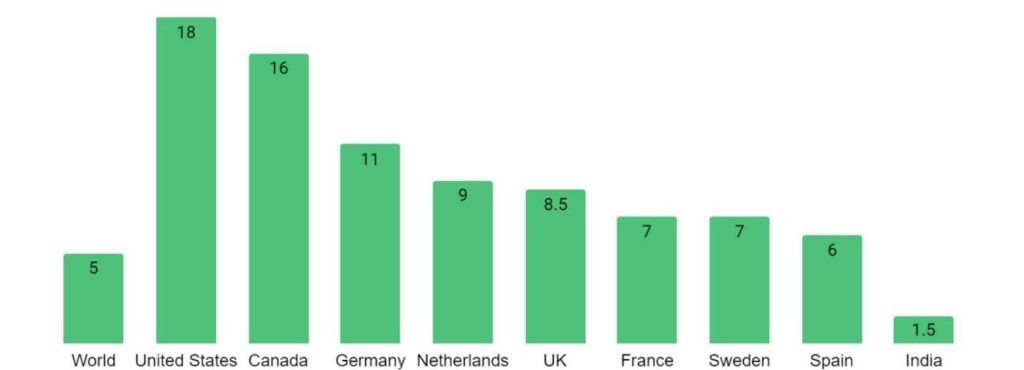

However, it is debatable whether choosing not to have children would have any significant impact on the environment. Current emissions per person differ considerably across countries. The disparity in individual carbon footprint is most visible between rich and poor countries. For instance, the average Indian would consume far less emissions than the average American or Canadian.

Lifestyle choices determine each individual’s carbon footprint. That is, what they consume and how much they rely on fossil fuels to produce electricity, generate heat, commute to work, and so on.

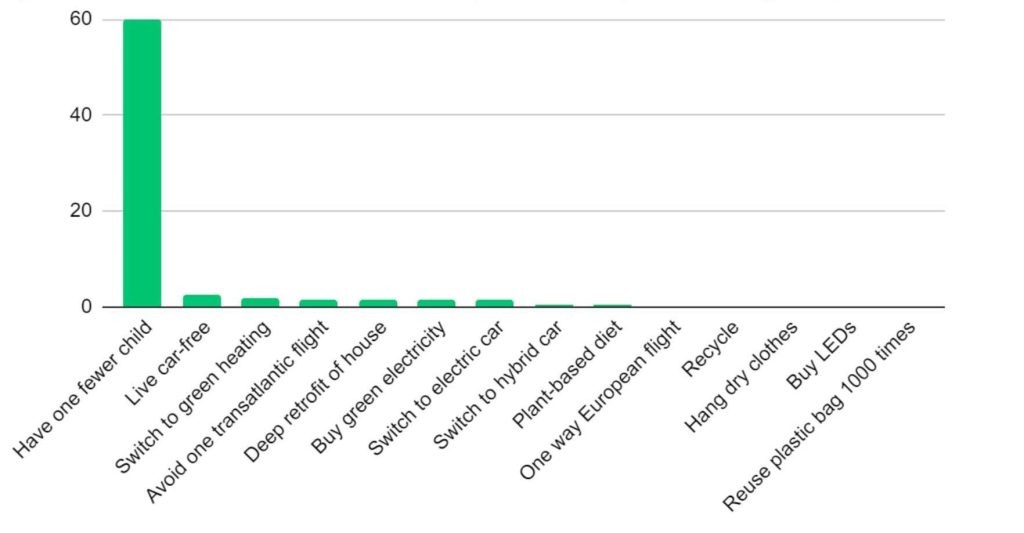

The graph above shows how different personal lifestyle choices (excluding government policies) can influence CO2 emissions. Having fewer children seems to be the most effective way to reduce emissions. However, these estimates assume that one’s descendant will maintain the same level of emissions into the future. This assumption is unrealistic because emissions per head are declining, or expected to decline, in most advanced economies.

In addition, changes in society are making drastic changes to the current use of resources:

- Many jurisdictions now have legally binding climate targets and/or carbon pricing schemes committing them to decarbonisation

- Climate policy will become more stringent over the next few decades as countries become increasingly pressured to act on climate change, and

- More children will grow up to vote, engage in climate activism, and support climate non-profits.

Photo by Mika Baumeister, Unsplash

Why Having Children Should Remain A Choice

Antinatalism might provide a useful perspective, but any government policy that attempts to reduce the rate of global population growth runs the risk of population imbalance, oppressive policing, and infanticide.

Alternatively, we can focus on ensuring intergenerational equity by creating liveable, sustainable conditions for our descendants. Individuals can assist with broader policy decisions by practicing a more conscious lifestyle. For example:

Reducing food waste

As the population grows, so will the demand for food. Everyone on this planet should be able to consume quality and nutritious food. Reducing our food waste means that unused food can be provided to those in need.

Smart water consumption

The efficient management of clean and safe water, as well as monitoring and recycling waste water are solutions that could solve water scarcity around the world.

Adopting a Plant-based diet

Meat products responsible for more greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per pound than plant-based foods. Learning to consume a nutritious, plant-based diet whilst reducing our meat consumption can significantly reduce our carbon footprint.

Small Steps to Big Changes

Small steps like these help ensure that our planet is a place where future generations can live sustainably. Larger steps, involving more complex sustainability measures, can change industry and build what the Thrive Project calls ‘thrivability‘: a state of existence that is ‘flourishing’ and beyond sustainability.

The Thrive Framework is a methodology for measuring the outcomes of sustainability projects. Thrive is dedicated to changing the debate around the environment. Thrive is a not-for-profit, for-impact organisation advocating activism on climate change that leads to greater well being, not less.

Visit the Thrive Project to learn more, subscribe to our newsletter, and stay informed about progress on sustainability measures. You can keep up to date by reading our blog, listening to our regular podcasts and joining our live monthly webinars featuring specialist researchers from a range of sustainability disciplines.