The facts on food waste point to a major global problem. Every year 1.3 billion tons of food is lost or wasted around the world. That creates serious threats to our food security, economies, and the environment.

It’s equivalent to throwing away US $1 trillion annually. Worse, an estimated 800 million people currently live in hunger. Further, with a global population approaching 9 billion, food output will need to increase by 60 per cent by 2050.

food waste, global hunger and the environment – what’s the connection?

Right now, there’s enough food to feed everyone on the planet. Yet, one third of food produced is either wasted or lost. Edible food thrown away by retailers or consumers is Food Waste. Food damaged as it transits along the supply chain is Food Loss. Reversing most of this wastage and loss would preserve enough food to feed 2 billion people. In effect, that’s more than twice the number of undernourished people across the globe.

As shown above, food waste tends to be more prevalent in high-income countries, whereas food loss is more prevalent in low income countries.

The Facts on Food Waste and the Environment

In addition, wasted food harms our environment because it directly impacts global warming. Once it is dumped in landfill, food waste emits greenhouse gases as it rots. In this way, an estimated 3 billion tons of greenhouse gas are emitted each year.

Today, many countries meet growing demand for food by increasing their agricultural production without reducing their food loss and waste. As a result, there are greater pressures on the ecology and our increasingly scarce natural resources.

Also, wasted food uses up energy, land, water and labour to produce. It takes up valuable energy resources for storage, harvesting, transport, packaging and sale. So, when we throw away perfectly edible food we are are effectively throwing away precious resources as well.

Why are we letting Good food go to waste?

There are many reasons for food waste. It differs from country to country. However, there are some key factors that influence behaviours:

- Income levels

- Urbanization

- Levels of economic growth

- Availability of technology, and the strength of supply chains

- Community habits and education

Thus, in low-income countries, food waste occurs mainly at the early and middle stages of the food supply chain. This is due to the standard of harvesting techniques, storage facilities, managerial expertise, and financial and technical limitations. By contrast, medium and high income countries experience most of their food loss and waste at later stages of the supply chain. Therefore, the behaviour of consumers in industrialized countries plays an important part.

Some of the main drivers of food waste are:

- Poor Weather (produce left in fields)

- Pests

- Disease

In 2020 there was a surge in food loss and waste with restrictions on movement and transport from the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, food waste had been significant long before then.

Rich Countries Waste What Sub-Saharan Africa Produces

The industrialized countries in North America, Europe and Asia collectively waste 222 million tons of food each year according to the U.N. Environment Programme. That is nearly equivalent to the 230 million tons of food produced by countries in sub-Saharan Africa each year.

Why is so much food wasted in the United States?

The United States has the second highest food waste per capita in the world, behind Australia. Wasted food amounts to roughly 30% to 40% of total US production. The reasons for this go far beyond throwing out leftovers. Rather, a range of socioeconomic disparities, a lack of co-ordination, misunderstanding, ingrained beliefs and habits are to blame.

Let’s explore some facts on food waste in the United States:

- More than 80% of Americans throw away perfectly good food because they misunderstand expiration labels.

- Oversized servings and containers are becoming standard in US restaurants, fast-food outlets, grocery stores and homes.

- Consumers expect fruit and vegetables to be the ‘perfect’ shape, size, and colour. However, selling only ‘flawless’ produce means everything else is left to rot.

- Overstocking of supermarkets.

- A lack of accessible food rescue and recycling services.

Overall, the most wasted food type in the US is bread, with 38% of all grain products lost every year across the country. Second is milk, with 5.9 million glasses poured down the sink. That is followed by potatoes, of which 5.8 million are discarded each year.

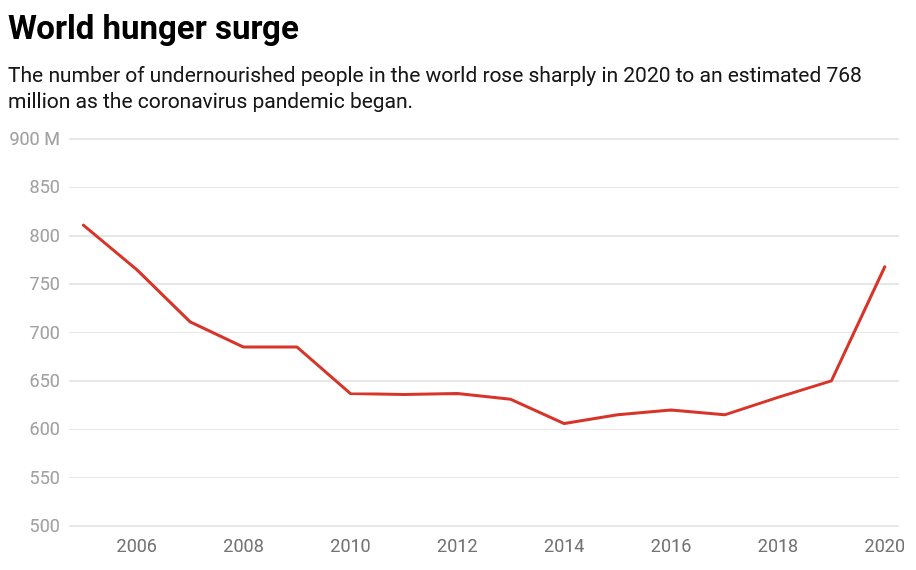

The challenges of ending global hunger

Global hunger was prevalent before the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. However, both the pandemic and the Ukraine war have exposed serious weaknesses in our food production and distribution systems. Today, those failures threaten the food security and nutrition of millions of people around the world.

In fact, the number of undernourished people globally continued to rise in 2020. In that year, between 720 and 811 million people experienced hunger.

Source: The Conversation

The Facts on Food Waste: Key Issues

Not surprisingly, there is more than enough food on Earth to feed everyone. Millions are going hungry, and it’s not because the world is unable to grow enough food. The main reasons are:

Climate change

Climate-related disasters such as extreme heat, droughts, floods and storms are diminishing agricultural productivity and destroying crops.

Conflict

The war in Yemen, for example, has resulted in an economic collapse. This crisis has led to the world’s largest food security emergency. Conflict and economic crises have caused more than 80% of Yemenis to live below the poverty line. Over 5 million people are on the brink of famine whilst nearly 19 million people will become food insecure by December 2022.

Inequality and poverty

Inequalities in social, political, and economic power cause uneven distribution of hunger and malnutrition. For example, large firms have disproportionate power over national food policies, local markets, smaller producers, and individual preference. Also, gender inequality and patriarchy often leads to poor outcomes for families. Women and girls can be sidelined from decision making which leads to poor decisions on the provision of food and nutrition.

Rising food prices

Food is becoming increasingly expensive due to unstable economies, war, and extreme weather events. In 2021, food prices rose by 28% in some parts of the world, the highest increase in ten years. For example, Sri Lanka’s worst economic crisis since its independence has triggered record price rises, 90% food inflation. Nearly four in every ten households in Sri Lanka have insufficient food consumption. Many also consume insufficiently diverse diets due to the high price of food.

Poor infrastructure

It’s no coincidence that most people who suffer from hunger live in rural areas lacking in basic infrastructure like drinking water, irrigation, and energy. Financing of infrastructure, including roads and energy grids, would help provide food security for millions of people worldwide.

Lack of information

Gathering information is the most critical challenge facing governments, donors and organisations mobilised to minimise hunger. They need to find out how much it will cost to fix problems, what interventions are likely to be most effective in solving them, and how that will impact the rest of the economy. The problems are complex and require careful, well researched strategic planning.

Lack of recycling

Excess food should be donated to the large network of relief organisations established to reduce global food waste. The International Food Waste Coalition (IFWC), for example, is a not-for-profit organisation, set up to coordinate action on food loss and waste in Europe’s hospitality and food service sector.

Solutions to reduce food waste and world hunger

A range of solutions is already available to tackle food waste and feed people in need:

- Good data: Working out where the major hot spots of food loss and waste are in the food production value chain.

- Innovation: Establishing new platforms like e-commerce for marketing or retractable mobile food processing systems.

- Investment in better equipment: Purchasing better harvest and storage solutions to avoid food loss for small and large producers.

- Government incentives: Enhance collaboration and action across private sector supply chains to address food loss and waste.

- Training in strong infrastructure, technology and logistics: Provision of sustainability education in cold chains and cooling technologies.

- Better food packaging: Relaxing regulations and standards on aesthetic requirements for fruit and vegetables.

- Redistribution: Using food banks to route safe surplus food to those in need.

- Shorter value chains: Facilitate access to consumers and create shorter value chains with farmers’ markets and faster rural-urban linkages.

- Improve equality and reduce conflict: Greater political stability plays a vital role in solving world hunger.

- Better pricing in Supermarkets: Large and small retailers can reduce the prices of imperfectly shaped vegetables or those that have a shorter shelf span.

- Re-using food for animals: Food no longer fit for human consumption should be reused to feed animals, make compost, or produce bioenergy.

- Safeguard our land and oceans: Restoring our ecologies so that we can produce safe and sustainable food.

- Revision of sell-by dates: Reassess use-by dates so that safe food is not discarded.

- Reduce landfill: Better disposal of waste to reduce greenhouse gas-emitting landfills. This includes recycling and the transformation of waste into fuel.

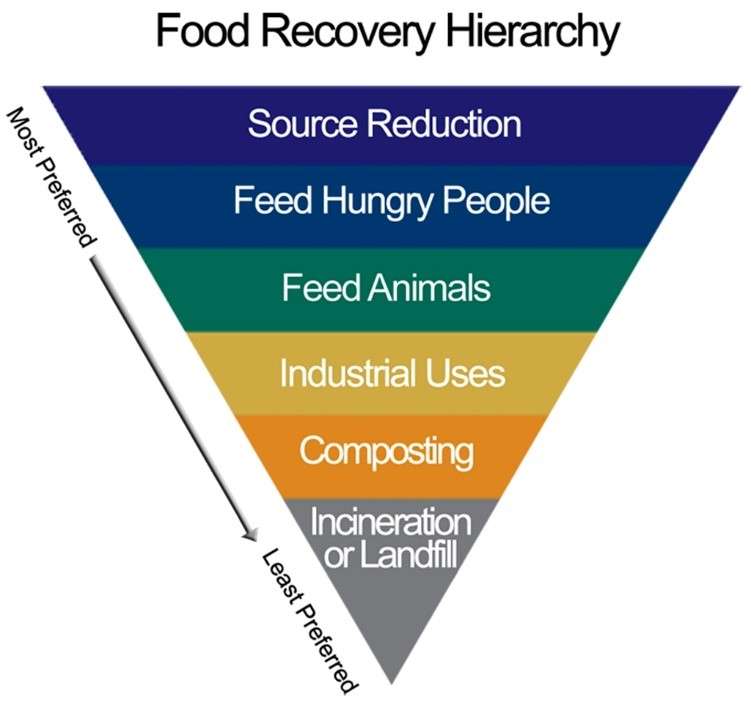

The Food recovery hierarchy

A food recovery hierarchy developed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) below illustrates the most effective ways to address food waste. The top levels of the Hierarchy are the most favourable, flowing down to the last level of waste that is sent to landfill.

What Can You Do About Food Waste?

Remember that small efforts add up, so we shouldn’t just rely on governments and institutions to tackle food waste and loss. Here’s what you can do to reduce food waste and solve world hunger!

- Start with a shift to a healthy and sustainable diet.

- Don’t serve yourself more than you can eat and request smaller portions of food in restaurants.

- Be a mindful shopper! Buy only what you really need to reduce the amount of food being thrown into garbage.

- Plan your meals and make a detailed shopping list.

- Keep track of food expiration dates and store food accordingly.

- Think about how can store and recycle leftovers.

- Create awareness among your family, friends and community to inspire others to help stop food wastage.

- Donate to those in need of food.

Small steps like these will help make our planet a place where future generations can live sustainably. Larger steps, involving more multiplex sustainability measures, will change the food industry and make the elimination of hunger possible.

Is achieving zero hunger realistic?

The WFP says it needs an additional $6.6 billion beyond its annual budget to alleviate world hunger today. However, it takes more than money to solve hunger. Now that we know the facts on food waste, we can no longer continue to let it continue unchecked.

With less than a decade left, the world is not on track to meet the goal of ending world hunger. High levels of inequality is unsustainable, and we cannot build sustainable societies in an unsustainable world.

However, achieving zero hunger by 2030 is entirely feasible if we take achievable steps right now. We have the facts on food waste and unequal distribution and we already have the solutions to hand.

Complex problems require informed solutions. So, our national and organisational strategies require access to the best available data.

The Thrive Framework

At THRIVE, we want to instil the idea that sustainable solutions not only prevent disaster, but offer the potential for societies that flourish.

At its core, sustainability simply means the ability to continue, to survive. ‘Thrivability‘, by contrast, is the next step, beyond sustainability. THRIVE believes that humanity can do better with the knowledge currently available to us.

The THRIVE Framework examines issues and evaluates potential solutions in relation to this overarching goal of thrivability. It is about making predictive analyses using modern technology that support environmental and social sustainability transformations.

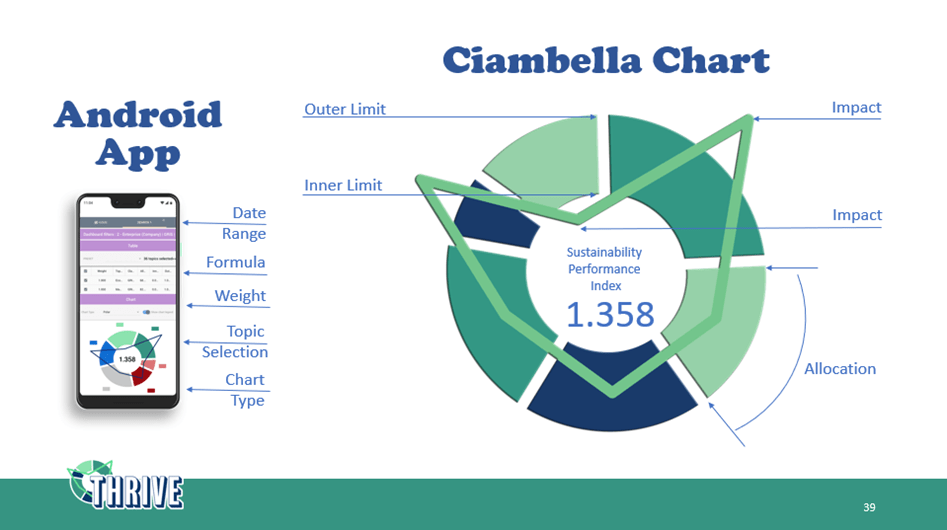

We recognise that human happiness can sometimes compete with environmental wellbeing, which is why we use our ciambella chart (below) to illustrate the ‘thrivable zone’. This is the area between a ‘social floor’ (the minimum required for people to live happy lives) and an ‘environmental ceiling’ (the maximum damage that we can do to the environment before it becomes unsustainable).

Overlaid on these thrivable zones are visual measurements that show impact – whether something is inside the thrivable zone – or exactly where it falls short.

To learn more about how The THRIVE Project is researching, educating and advocating for a future beyond sustainability, visit our website. You can follow our informative blog and podcast series, as well as find out about our regular live webinars featuring expert guests in the field. Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates.

GOT A QUESTION ON THIS TOPIC?