One the main reasons people choose to migrate is economic. Migration represents a vital pathway to a better life for many individuals and families. Therefore, poverty and migration are often closely linked.

However, the circumstances that give rise to migration are complex. Migration is often perceived as either ‘voluntary’ or ‘forced’. Yet, such distinctions are meaningless, as many migrants don’t have a great deal of choice. The question is more to do with whether they have the means, and what obstacles they must overcome to do so.

Also, while severe economic disparities between countries will drive many people to migrate, solutions to world poverty are much more complex than simply moving poor people to rich countries.

In this article, we look at the variety of reasons people migrate and the factors that will influence their decision. We also investigate how migration impacts world poverty, for better and for worse.

The Main Drivers of Migration

The fundamental factors that influence migration are:

- Economic

- Political

- Social

- Cultural

- Demographic

- Ecological

Perceptions of Migration

The common perception of migrants is an influx of poor people from developing or low-income nations seeking to escape poverty. The assumption is that all migrants are very poor and arrive in the host country simply because they are desperate. Therefore, critics of immigration tend to ask why we should still be accepting migrants when “we’ve been providing aid for a long time.” The logical solution to migration from this point of view is to increase foreign aid instead.

However, people from low-income countries are not necessarily more likely to migrate. In fact, emigration rates are low in the poorest countries. Whilst escaping poverty is a primary motivation, there are many other factors that influence the decision to migrate.

Migration as a development Strategy?

Migration is part of a much larger phenomenon. It certainly represents an avenue for better economic opportunities, but it can also provide benefits to both countries.

Indonesia actively promoted labour migration as a national development strategy. The goal was to address poverty and domestic unemployment in the country by encouraging work elsewhere, enhancing foreign direct investment through remittances.

Generally, immigrants expect to maximise their expected income and achieve a better standard of living. However, many have strong cultural and familial ties to their home country, and often send back a good portion of their income to support family members.

Furthermore, income inequality is higher in developing and emerging economies than in it is in advanced economies. Unfortunately, income inequality has continued to rise in emerging economies over the past three decades. That means the option of migrating is often not available to the poorest people. In addition, ethnic tensions and discrimination can worsen their plight.

What Affects the Reasons People Migrate?

An individual or family’s ability to migrate is affected by:

Migration costs

Migration is often expensive. People who migrate face liquidity constraints. This lowers migration rates if people simply cannot afford to leave. At higher levels of household income, any additional income may relax liquidity constraints. This will tend to increase the desire to migrate.

However, at even higher levels of household income, where liquidity constraints are less binding, additional income may actually reduce the desire to migrate.

Social inclusion or exclusion

Migrants may find it challenging to integrate into a new society. Language barriers and difficulties in finding employment may lead to social exclusion. Therefore, strong networks and integration policies are important in helping immigrants adjust to their new culture.

Skills and knowledge

The ability to transfer skills and knowledge to a destination also determines whether people can migrate. For example, Australia is currently seeking migrants to fill jobs in the farming and agricultural sector. This is largely due to a shortage of labour within Australia’s rural areas which allows the import of a wide range of skills.

How does migration impact poverty and inequality?

Work is one of the key reasons people cross national borders, whether driven by economic conditions at home, employment opportunities, or both. Yet, migration has both positive and negative impacts on poverty.

Labour migration is commonly perceived as the most effective way to improve the lives of the poor, and the poorest groups of people are disproportionately represented in crisis migration. However, migration does not always relieve distress. It can also send low-income earners into further debt and poverty.

Advantages

- Primarily, migration provides a way to enhance income. Moreover, it helps households buffer the risks associated with investing in more productive activities. Remittances coming in from work performed in other countries will fund education, household spending, and other investments in the home country. Thus, international migration and remittances have been shown to significantly reduce the level, depth, and severity of poverty in the developing world.

- Emigration can relieve labour market and political pressures as a result of remittances sent home. Migration can also help destination countries increase trade and financial investment from abroad and thereby enhance their economic growth. Additionally, it leads to an increase in migrant communities (diaspora) and exchange in things like technology transfer, tourism, and charitable activities.

- The return of highly skilled migrants who have acquired specialised knowledge and skills (e.g. engineers and scientists) which can help improve research and development programs in the home country.

- Migration can also help individuals and their families improve their social status, build up assets, and improve their quality of life in a new environment.

- Finally, cultural diversity and understanding is enhanced by the influence of migrant communities in host countries. This can improve the quality of life, and diversity, in those countries, as well as improve their trust in developing countries.

Disadvantages

- Again, migration doesn’t always reduce poverty. Some people may even find themselves in worse circumstances after moving to another country. This can be due to the high costs involved, the conditions in host countries, and barriers to mobility.

- The poor have fewer options to migrate and often migrate to areas with lesser returns. The biggest impediments to emigrating are a lack of opportunity, and high costs. This means smaller profits and, most likely, less alleviation from poverty.

- The involvement of criminal gangs in trafficking and people smuggling continues to pose an enormous challenge. Thus, individuals and families may find themselves experiencing harassment and violence, and the prospect of falling victim to criminal organisations.

- Irregular or undocumented migration can lead to deaths and disappearances. In addition, there are far too many instances of people who have died attempting to migrate by sea.

- Migration through irregular channels can make people even more vulnerable. For example, people in desperate situations may decide to commit all of their savings to illegal movement. As a result, many migrants are arrested or sent back to their country of origin.

- Migrant women, in particular, face much hardship on their journeys. They also experience significantly more challenges accessing employment, training opportunities and healthcare at their destinations.

The reasons people migrate: Case Studies in Immigration

Venezuela

Venezuela was once a prosperous, oil-rich country which had been dependent on the fossil fuel market since 1920. Its downfall is a classic example of poor long term investment.

Venezuela chose to rely solely on foreign capital from oil to boost its local currency. As a result, it neglected to invest in other vital industries which could have served its people long term, like agriculture and manufacturing.

Since the 1950’s, Venezuela has undergone decades of social and political upheaval. Hugo Chavez’s militant rule from 1958-2013 forced the foreign-run oil industry to reprise their earnings to local oil industries. Thereafter, the country has witnessed an erratic series of successes and failures in response to the global oil price cycle.

Chavez also played a large role in Venezuela’s rejection of free-market reforms. This led to some of most severe cases of corruption in the oil industry, followed by damaging inflation, and six recessions. Thus, many Venezuelans were forced to leave well before this century’s worst recession.

By 2016, high inflation, increased living costs, and the despotism of leaders such as President Nicholas Maduro, made living for Venezuelans unbearably difficult. The United States added to that pressure by placing sanctions on Venezuela designed to strangle its earnings from oil.

Discrimination in Latin America

An historical series of political-ideological mishaps, and the consequence of several loans from the International Monetary Fund since 1983, has forced a majority of Venezuelans to flee to neighbouring Latin American countries. Venezuelan migrants settled in Colombia, Peru, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay. Here, lack of financial security has forced many to work illegally for little to no pay.

Furthermore, many have experienced discrimination that ranges from aggression and verbal abuse to mob killings driven by xenophobia. Fortunately, some Venezuelans had adequate finances and were able to find refuge in developed countries like the US and in Europe.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is experiencing an ongoing political and economic crisis which escalated with the rise of the populist Rajapakshe political family in 2006. The country has a history of unresolved ethnic violence dating back to the early 70s. Meanwhile, at least 1 million young Sri Lankans have left the country due to its economic insecurity.

Minority Sri Lankan Tamils in the North and North-East faced racial discrimination, violence, and pogroms in pre-civil war times. Yet, even after the civil war ended in 2009, discrimination against Tamils and other minorities continues in the country. Sri Lankan Tamils live abroad as diaspora communities. They have strengthened their cultural identity overseas and rarely visit their ancestral homes due to fears of unwarranted persecution and non-judicial arrests.

Those who were unable to legally escape abroad, especially poor and minority groups, have attempted risky, undocumented departures by boat. Sadly, this method of escape has led to a number of fatalities.

Family separation

Unlike Venezuela, Sri Lanka does not have oil deposits, nor sufficient resources, to manage a growing population of 21+ million people. The country has failed to improve the welfare of its lowest earning families.

As a result, many female breadwinners must leave their children under the care of their husbands or extended family to go to work in the Middle East. These women are often employed in unskilled jobs (i.e. housemaids, cleaners) and sometimes face sexual and physical abuse by their employers. Also, their abandoned children have experienced abuse and rape by relatives or guardians. There are many cases of learning difficulties associated with abandonment as well.

Sri Lankan foreign workers are primarily based in Saudi Arabia and send their income home as remittances to feed their families. However, recent lockdowns to contain COVID-19 have forced these employees out of work. Consequently, they have been stranded in a foreign country away from their families and unable to earn money.

Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar

Rohingya are a Muslim ethnic group that has lived for generations in the Rakhine state of Myanmar. However, Rohingya are not recognised as an ethnic group in the Buddhist-dominant country. Therefore they are considered stateless and face relentless persecution and discrimination.

Between 2016 and 2017, state-sponsored genocide forced millions of Rohingya to flee to neighbouring Bangladesh. Some live in refugee camps like Cox Bazar, the world’s largest refugee camp. Enforced poverty in that country restricts them from seeking better education or legal assistance to find ways to improve their social status. Instead, Rohingya are employed as cheap, illegal labour on construction sites. This means they are constantly at risk of deportation to host countries in South-East Asia.

Mahmoud Sulaiman from Unsplash

War in Syria

War and ethnic repercussions are the most powerful reasons people migrate. Many are simply forced to leave. The Syrian War started in 2011 and people fled the war-torn country in droves. Worsening civil discourse with anti-governmental groups had snowballed into a power-play between foreign powers leading to the commencement of regional conflicts between Kurds and Turkish forces.

The mass exodus of Syrians was an attempt to escape the trauma of war, forced conscription, or to sustain their families using remittances from foreign work.

The Middle East is comprised of several landlocked countries which share similar cultural roots. Many Syrian migrants have escaped to different parts of Europe. However they have had to face rising xenophobia and Islamophobic dialogue from right-wing political circles. Not unlike the Ukrainians escaping Russia’s 2022 invasion, Syrian migrants face severe challenges. Many are living in refugee camps with little access to food and water, education or employment in their host country.

Policies to Address The Reasons People Migrate

Given the risks and potential benefits of migration, governments must carefully consider the impact of their immigration policies. These can affect migrants in host countries as much as their families in their home countries, and can drastically reduce poverty.

Therefore, to maximise the benefits of migration and limit risk, governments must:

- Manage migration at the national level and plan for internal mobility, especially for refugees.

- Create opportunities for legal migration with the granting of temporary visas, including for low-skilled migrants where the reasons people migrate is to meet the needs of local labour markets.

- Ensure migrants’ access to human rights and their legitimate entitlements under national law when arriving in the host country.

- Provide low-cost and secure mechanisms for sending remittances home or investing them in low-income communities. This will allow foreign workers to send more money home to their families.

- Build support for positive diaspora activity to maximise the impact of remittances in helping to develop the country of origin.

- Increase and diversify safe, regular and orderly migration pathways in line with demand for migrant labour, and make these easier to access.

- Lower the costs and bureaucratic requirements for those wishing to migrate, and facilitate safety nets for migrants fleeing war and persecution.

- Provide access to state-funded mental healthcare for migrants who have experienced trauma, thereby assisting them to gain induction into the workforce.

Conclusion

Economic analysis suggests that migration to industrialised countries may lead to gains of up to US$300 billion a year by 2025. This benefit is shared equally between people in developing and developed countries. Much of the gain comes from the migration of unskilled workers to meet labour market needs.

If managed well, migration has the potential to support the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and improve lives on a global scale. It is important, therefore, that development policy and strategies to reduce poverty take account of the complex issue of migration.

Poverty is clearly one of the fundamental reasons people migrate. However, it is not the only reason, and migration can both improve and worsen economic outcomes in different circumstances.

More evidence on the mechanisms through which migration impacts poverty is required. For example, better longitudinal data would help us to better understand the reasons people migrate and migration pathways, allowing governments to target policies more effectively. Further, we need a balanced debate about migration: one that ensures we do not stop it benefitting poorer communities, but one that also tackles its negative consequences.

The Thrive Framework

At its core, sustainability simply means the ability to continue, to survive. ‘Thrivability‘, by contrast, is the next step, beyond sustainability. THRIVE believes that humanity can do better with the knowledge currently available to us. We want to instil the idea that sustainable solutions not only prevent disaster, but offer the potential for societies that flourish.

The THRIVE Framework examines issues and evaluates potential solutions in relation to this overarching goal of thrivability. It is about making predictive analyses using modern technology that support environmental and social sustainability transformations.

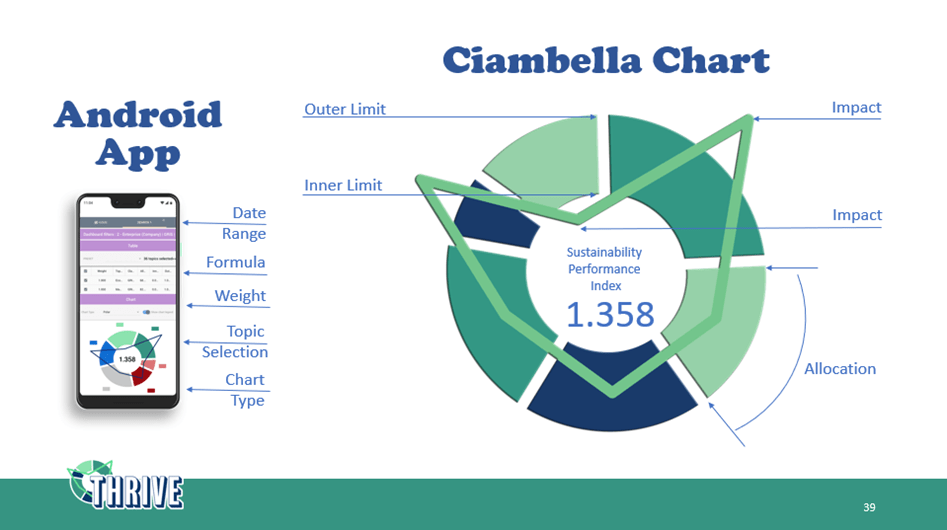

We recognise that human happiness can sometimes compete with environmental wellbeing, which is why we use our ciambella chart (below) to illustrate the ‘thrivable zone’. This is the area between a ‘social floor’ (the minimum required for people to live happy lives) and an ‘environmental ceiling’ (the maximum damage that we can do to the environment before it becomes unsustainable).

Overlaid on these thrivable zones are visual measurements that show impact – whether something is inside the thrivable zone – or exactly where it falls short.

To learn more about how The THRIVE Project is researching, educating and advocating for a future beyond sustainability, visit our website. You can follow our informative blog and podcast series, as well as find out about our regular live webinars featuring expert guests in the field. Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates.