Human rights violations affect millions of people from all economic, social, and cultural backgrounds. For instance, 5.3 million children under the age of five died in 2018, and around 821 million people were undernourished in 2017. Additionally, 11 million were displaced in 2018, escaping Iraq. Finally, around 55% of the world population still has no access to social protection. These people deserve the right to live a thrivable life as much as the rest of us. But there is much to do if the world is to collectively enjoy thrivability.

What is Thrivability?

Thrivability is a term that represents a cultural vision that goes beyond sustainability. Merely sustaining the world is risky. We need a buffer, a cushion of abundance to stay above the sustainability threshold in times of trouble. Thrivability means ensuring the holistic well-being and flourishing of all life forms and ecosystems on Earth.

This comprehensive approach encompasses social, economic, environmental, and cultural dimensions, with the ultimate goal of securing the prosperity of both humanity and the natural world. We must consider the Systemic Holistic Model when evaluating the significance of the consequences if the challenges are left unaddressed. It’s essential to assess the scale of these challenges, the scope of the system they affect, and the necessary shifts required to ensure a future in which individuals can fully exercise their right to develop and thrive.

The concept of thrivability is a response to the numerous crises our planet confronts, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, inequality, and economic instability. It signifies a shift from reactive efforts to mitigate harm to proactive measures that foster the flourishing of all living beings and ecosystems.

Beyond Sustainability: Human Rights as a Centre of Sustainable Development

Human rights are an essential condition for sustainability and climate justice. However, this is a complex wicked problem, where pushing for some human rights may sometimes infringe on other values.

The United Nations (UN) embeds over 90% of the Sustainable Development Goals in human rights treaties. In addition, the 1992 Rio Declaration states in the very first principle: “Human beings are at the centre of the concerns for sustainable development. They are entitled to a healthy and productive life in harmony with nature” (Antrim. L.N, 2019).

The pursuit of inclusive, equitable, and sustainable development can only take place when human beings are the central concern. Therefore, sustainable development is a process primarily considering human beings and human rights. Undoubtedly, it is critical to apply a human rights-based approach to guide global policies and measures that are designed to address issues of sustainable development.

In 2019, the UN’s Human Rights Council highlighted a set of good practices regarding climate justice. Climate justice embodies our right to access “safe, clean, healthy, and sustainable environments“. Portugal and Spain were the first countries to declare the rights to a healthy environment in their constitutions (the former in 1976 and the latter in 1978). According to the UN, 80% of UN’s members recognise the right to a healthy environment within their laws, leading to stronger environmental policy and law. The right to a healthy environment includes access to:

- clean air,

- water,

- sanitation,

- sustainably sourced food, and

- healthy ecosystems.

The right to a healthy environment is a delicate balance and an important step to providing global human rights.

What are basic human rights?

Human rights are based on principles of dignity, equality, equity, and mutual respect shared across cultures, religions, and philosophies. They constitute fair treatment, treating others fairly, and having the ability to make genuine choices in our daily lives (Schlosberg & Collins, 2014).

A series of international human rights treaties have been adopted since 1945, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations on 10 December 1948. The declaration sets out the basic rights and freedoms that apply to all people. Drafted in the aftermath of World War 2, it has become a fundamental document inspiring several core international human rights instruments.

As individuals, we all have rights including but not limited to:

- The right to life, liberty, and security of a person.

- Social protection, including an adequate standard of living, and the highest attainable standards of physical and mental well-being.

- The right to work in just and favourable conditions.

- The right to education and enjoyment of the benefits of cultural freedom and scientific progress.

- Freedom of speech, thought, conscience, and religion.

- Freedom of opinion and expression.

Although there is considerable consensus on the need for human rights, there are issues with enforcing them. Human rights must be codified into law before they can be effectively enforced within a country. Legal recognition and protection ensure that these rights are not just lofty ideals but concrete obligations that governments and institutions must uphold. By incorporating human rights principles into a nation’s legal framework, they become binding obligations that can be upheld in courts, allowing individuals to seek redress when their rights are violated. This legal foundation also provides a basis for international oversight and accountability. Without legal backing, human rights remain vulnerable to neglect and abuse, making their formal recognition and enforcement essential for a just and equitable society.

Beyond sustainability: Development rights

The right to development is at the core of the Sustainable Development Goals; the right to food (championed by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization); labour rights (defined and protected by the International Labour Organization); gender equality (promulgated by UN Women); and the rights of children, indigenous peoples, and disabled persons.

In particular, the right to development (or the right to thrive) belongs to everyone both individually and collectively, with no discrimination and with their participation. That is to say, the pursuit of economic growth is not an end in itself. There are finite resources to consider and the boundaries between what humans need to survive and how much the environment can sustainably provide.

In summary, the right to development puts people at the centre of the development process, which aims to improve the well-being of the entire population and of all individuals on the basis of their active, free, and meaningful participation, as well as in the fair distribution of the resulting benefits.

A long way to go!

Despite progress in ensuring human rights, we still fall short in many parts of the world. The use of context-based metrics in the pursuit of achieving these science-based targets reveals how far things need to shift to become sustainable.

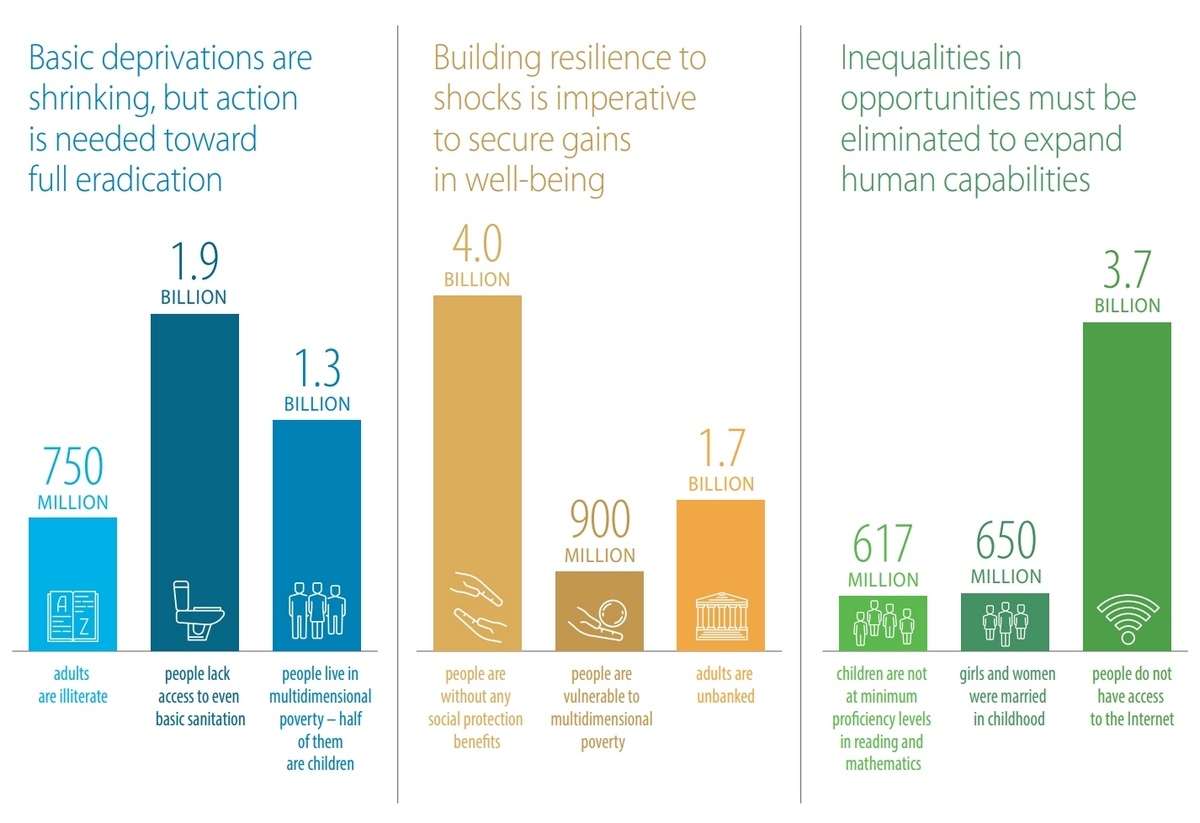

People are healthier and more educated and have access to more resources than at any time in history. However, there are many extreme deprivations (Figure 1). In particular, the least developed countries still suffer from high levels of poverty, illiteracy, and under-five and maternal mortality. Additionally, millions of people lack access to basic environmental resources such as air, water, and shelter. Even so, those who moved out of poverty may still be vulnerable to shocks, disasters, and unexpected health or job changes that could push them back into poverty. Social protection systems fall short of reaching the world’s most vulnerable people. At least one social protection benefit covers only 45% of the world’s population effectively.

The remaining 55%—as many as 4 billion people—are left behind.

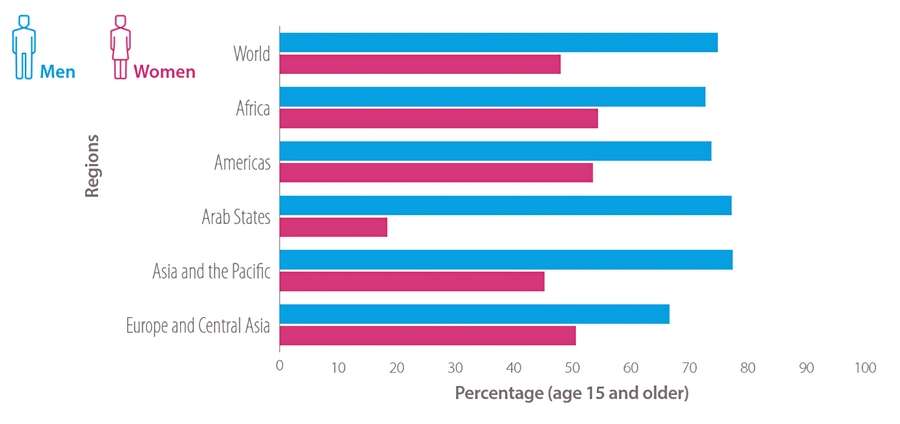

Women make up half of the world’s population. However, in 2017, the labour force participation rates for women were 26.5% lower than for men (Figure 2). Despite many women being employed in developing countries, 92% are in informal employment. Informal employment involves insecurity, lower earnings, and poor working conditions.

Poverty is still a concern

More than one-third of employed workers in sub-Saharan Africa live on less than $1.90 a day. Hence, having a job does not guarantee a decent living. In fact, 8% of employed workers and their families worldwide lived in extreme poverty in 2018, despite a rapid decline in the working poverty rate over the past 25 years.

In addition, many human rights violations disproportionately affect the poor. Discrimination against people living in poverty is extensive and widely tolerated. Approximately 135 million suffer from acute hunger largely due to man-made conflicts, climate change, and economic recessions.

The world is not on track to ending poverty by 2030. Politicians, service providers, and policy-makers often neglect or overlook people living in extreme poverty due to their lack of political voice, financial status, and social capital. The issue is that not dealing with extreme poverty now creates bigger problems later into the future that will affect everyone.

Moving Forward

Nations have an international obligation to prevent and protect human rights. As individuals, we are entitled to demand our respective governments protect and fight for those rights. We have freedom of speech and the right to engage in political activism in democratic societies. For example, in Australia, people demand the government address the climate crisis. The climate crisis potentially threatens human rights.

There is a lack of political will, particularly in countries with non-democratic systems or with emerging democracies. Political conflicts and tensions exacerbate this. Not to mention, governments face challenges in promoting human rights due to a shortage of institutional capacity and/or resources.

However, we can raise our voices for those who are experiencing disadvantages. We need to spread the word and collectively demand that all countries should have equal opportunity to thrive and develop for the betterment of all humanity. All of us can encourage universal cooperation to work as a team for a thrivable future. We can help human rights to become ingrained in all that society strives for. But it needs to be a cultural shift far beyond a sustainable level.

why Is it essential that we focus on Thrivability as something beyond sustainability?

Thrivability matters because it overwhelmingly addresses the interconnected crises, above sustainability, and ensures equitable access to resources and opportunities. It encourages ethical and eco-conscious practices, driving innovation and circular economies that prioritise long-term well-being over short-term profits. With a focus at this level, human rights can be equally supported all over the world.

Thrivability represents a cultural shift and lifestyle that promotes the well-being of everything because humanity’s well-being is intricately tied to the planet. As a species, we cannot reach our full potential in isolation. Our relationship with the well-being of the world directly affects our contentment, peace, and harmony. Witnessing thrivability practices inspires gratitude and appreciation. The amazing experiences that the world provides fill us with awe and wonder. Witnessing pain and suffering tends to cause negative emotions which hinder our potential to flourish as a society. Depriving ourselves of the gifts of thrivability diminishes our meaningful existence. Pure sustainability won’t suffice. In order to achieve our highest potential, we must ensure the entire world thrives.

Can you be a voice for the voiceless to protect their rights to thrive? Are you willing to reach out to government representatives and push for sound policies that align with worldwide thrivability? Are you willing to spread the concepts of a thrivable lifestyle to others in your community? Can you stand up when you see injustice and ensure the respect of people’s rights in your everyday life?

We may be one voice in billions, but a cultural shift starts with people sharing an idea. That’s not hard. When enough people share an idea, it becomes a part of everyday life. Thrivability being a part of everyday life is a goal worth striving for. Share the idea of thrivability to the world today.

achieving the United Nations Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs) and how they link to thrivability

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include SDG1, which aims to “End poverty in all its forms everywhere”. It’s tied to the human right of individuals to develop and thrive, as poverty is a barrier to human flourishing.

SDG2 centres on “Ending hunger, achieving food security and improved nutrition, and promoting sustainable agriculture”. This plays a crucial role going beyond just addressing hunger. It also emphasises sustainable agriculture as a means to empower small farmers, promote gender equality, eradicate rural poverty, and contribute to the overall well-being of communities.

SDG1 and SDG2 can create conditions that support the human right of all people to develop and thrive. We can break the cycle of poverty and ensure a better future for everyone.

A Thrivable Framework

The THRIVE Framework helps us address extreme poverty and hunger. It is fundamental in identifying the significance of eradicating deprivation and ensuring access to basic resources for all. We must also consider the scale of poverty and undernourishment challenges. This allows us to highlight the need for strong sustainable solutions to uplift disadvantaged populations. We need a cultural shift to move from mere sustainability to rampant thrivability. But in the scope of things, we must consider the complex wicked problem that poverty and hunger exist in.

This holistic approach aligns with the THRIVE Framework’s core principles. It recognises that human rights, poverty reduction, and food security are integral to achieving thrivability. We can address these challenges within the Systemic Holistic Model and place people at the centre of the development process to ensure the humane right to thrivability.

The THRIVE Project actively advances the UN SDGs through a variety of initiatives. These include webinars, blogs, and an extensive podcast series. Our newsletter serves as a platform to prioritise “thrivability” over mere sustainability. Sign up for our newsletter to stay informed about the pressing issues that impact these goals and receive regular updates on our efforts to contribute to their achievement. Together we can spread the news and give everyone the right to thrive.