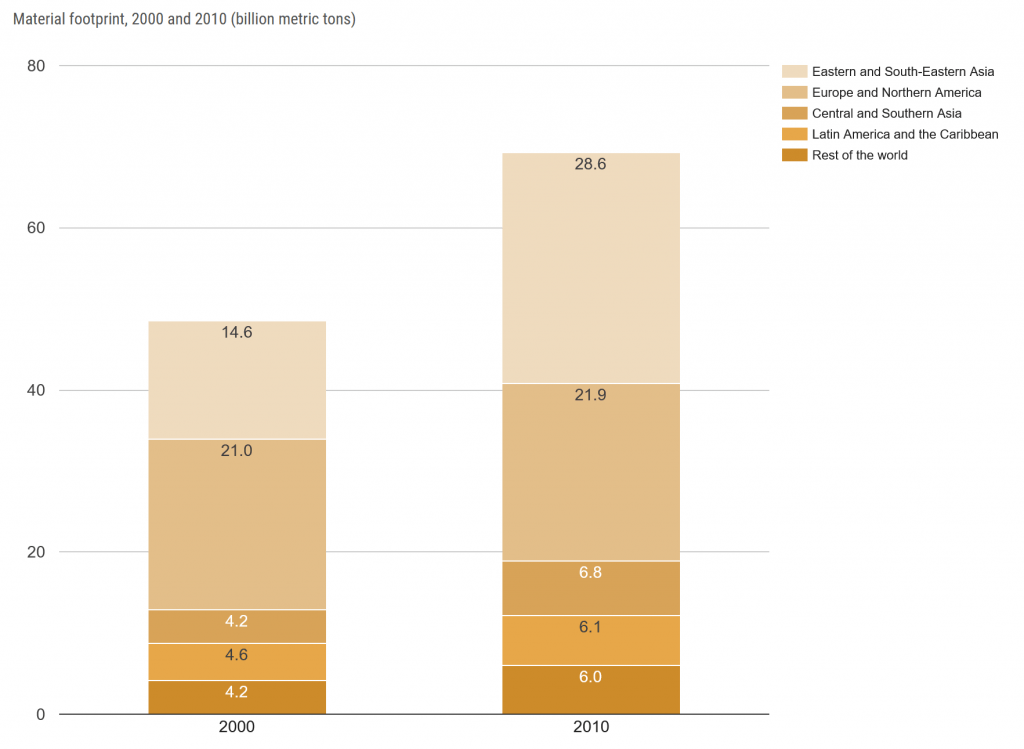

For many of us, overconsumption is a way of life. The desire to collect more than we need often drives us to take more and more from our planet. Between 2000 and 2017, the world’s material footprint has surged by 70%. This means we consume the resources our struggling Earth makes in a year, in only nine months.

By 2050, an extra 2-3 billion consumers could emerge, as more people make enough money to live in comfort. With potentially 9.8 billion people living on our planet by then, we will need to produce more to meet our desires.

When we reshape nature for our own uses, we often take more than environments can produce. By cutting down trees for agriculture, and plundering fish from our oceans, landscapes become less able to provide resources in the future. This harms animals, and pollutes the areas they live in, reducing biodiversity. For instance, overuse of resources and agriculture has harmed 75% of extinct plants and vertebrate animals. Without animals, lands and oceans can no longer provide for anyone. This means we could lose all the gains we’ve made in bettering our lives over the past 50 years.

Overconsumption and Waste

Our Earth can only create a certain amount-after this, it cannot recover. If we continue as is, we may need nearly three Earths worth of resources to preserve our livelihoods. Yet despite this, much of what we take goes unused. For instance, one-third of all food is wasted. $1 trillion worth of produce rots in our bins and spoils due to bad transportation and harvesting practices. Meanwhile, over 820 million people struggle from a lack of food.

COVID-19 has disrupted trade routes and economies the world over. However, it has also given us an opportunity to rethink how we live and consume. One thing is clear-if we keep going as we are, our world will have nothing left.

To provide comfortable lives for our growing population, we need to do more with less. If we can figure out why we consume, we can find a way to change this.

Why is Overconsumption Prominent?

Those with means tend to take more than they need. While this can give immediate pleasure, it rarely lasts. Consumption for happiness often leads to debt and misery. In contrast, studies have found that joy usually comes from friends and natural spaces, not purchases.

People who strive to consume more tend to be less happy and suffer from lower self-esteem, more anxiety, and worse social relationships. In contrast, beyond meeting basic needs and comforts, greater incomes rarely improve people’s lives.

Three types of behaviours often drive overconsumption, including:

- The desire to own more than they need: Many seek to consume more, even if they lack room to store it. For example, in the USA, most middle-class families struggle to store their goods. As a result, one in ten households there rent storage units for their excess products.

- Throwing out products for more attractive ones: Many items are thrown out, and replaced with new ones, as they are meant to be used once. Often, people also discard functional goods for items with slightly improved looks or performance.

- Seeking a similar lifestyle to the rich: Many consume luxuries in an attempt to gain a wealthy lifestyle. From designer clothes to electronics and appliances, the desire for luxury is becoming normal.

While many seek to consume larger amounts, others struggle to survive. A 2004 study, for example, found that while North America and Western Europe hold only 12% of the world’s population, they take up 60% of global spending. In contrast, around half the world lives on less than US$5.50 per day.

While many nations have come together to encourage responsible consumption and production patterns, efforts have struggled.

Why Current Solutions to Stop Overconsumption Fail

While efforts have been made to reduce overconsumption, these often focus on switching out products for less harmful alternatives. While many favour this approach, people tend to avoid such products. Some reasons for this include greater costs, worse performance and a distrust of marketing focused on sustainability. Though products often use fewer resources to make than in the past, rising overconsumption still worsens our impacts.

Governments often restrict access to impactful goods or use financial incentives to motivate behaviour. These tend to backfire, with restrictions often causing consumers and businesses to work around these.

Another common way to reduce overconsumption is through raising awareness of impacts. These often assume that people will make logical decisions based on costs and benefits. However, many tend to favour immediate outcomes rather than those in the long term. As a result, even if people seek to reduce consumption, they rarely act on this. For example, a survey of European consumers found that while 72% said they would buy sustainable products, only 17% actually did. This suggests that knowledge alone is not enough to make change happen.

Ways to Do More With Less

There are two methods that we can use to reduce consumption. These involve changing how consumers behave, or changing how products are made.

Changing Overconsumption Behaviour

Consumption is often driven by how people behave, and the ideals that drive this behaviour. Beliefs not only affect choices, but how people see their consequences.

The billions of small decisions we make combine to form significant impacts. If we consume less, we won’t need as many resources from nature. However, while many seek to live more sustainably, this tends not to happen. People rarely make optimal decisions, meaning efforts to change behaviour can be less effective, or even make things worse.

There are several reasons behind this:

- Many choices are habits

- Consequences are hard to see

- Sustainable consumption does not seem relevant

- Others influence behaviour

- It can be hard to follow through on choices

By exploring them further, we can find out how to solve these problems.

Many Choices are Habits:

People tend to follow habits in their daily lives. Habits, for example, make up over 40% of our decisions. For example, even though overeating, excess alcohol use and lack of exercise are known to harm people, 63% of deaths across the world stem from these. To change habits, we need to change the surroundings where they happen. For example, the city of San Jose, USA, shrunk their recycling bins to not be the same size, causing rubbish collected to fall by half. When people noticed the difference between the two, they were less likely to place recyclables in rubbish bins. Physical changes can make it easier to break habits.

Consequences are Hard to See:

We often struggle to know the consequences of our resource use. For example, without immediate feedback on increased usage, people often ignore long-term issues for immediate benefits. However, studies found that providing information on light bulbs’ long-term energy costs increased energy-efficient bulb purchases. By making consequences easier to notice, people are more likely to act.

Sustainable Consumption Does Not Seem relevant:

People across the world are concerned about the environment. However, they often fail to act for several reasons. For instance, many believe that while climate change is important, it will not affect them directly. Concepts that seem abstract to people are usually ignored as they feel distant. However, showing information that relates to people personally can make an impact. A California study found that showing the health impacts of their energy use reduced consumption by 8%. This more than doubled (to 19%) for parents, likely because of fears that health impacts may affect their children. Showing the direct impacts of actions on people and their communities can reduce consumption.

Others Influence Behaviour:

How people view themselves and others often dictates action. This is most visible when people are uncertain on what to do. People tend to follow what they believe social norms are, to avoid embarrassment. For example, a study found that consumers were more likely to buy sustainable meat products if they thought others were doing so. How people identify themselves also affects how willing they are to listen to messages. Information coming from within their social groups, for example, is often more accepted than those from outside.

It Can Be Hard to Follow Through on Choices:

The way that people receive choices can affect decision making. If sustainable options are harder to access, people are often less likely to select them. Even small requirements, such as paperwork can reduce the chance of picking a choice. One way of fixing this is to provide a sustainable option as the default. A German study found that 68% of people would select a renewable energy supplier when it is the default option. This is reduced to 41% when conventional energy is the default. By making sustainable choices as easy as possible, people are more likely to maintain them.

There are many ways to change behaviour. By changing the context in which people make choices, we can reduce consumption without stopping it altogether. If we only consume what we need, we can live happy lives while giving the Earth a chance to recover. However, the products that businesses produce often add to how much we consume. How can they reduce their impacts?

Redesigning products and services to be reusable

Many items are made to be replaced in the short term, motivating people to buy newer products. While they still work, goods tend to lose functionality as they age. Combined with difficulties and costs in repairing these, people often throw them out. This usually leads to further waste and resource consumption to meet demand for new items.

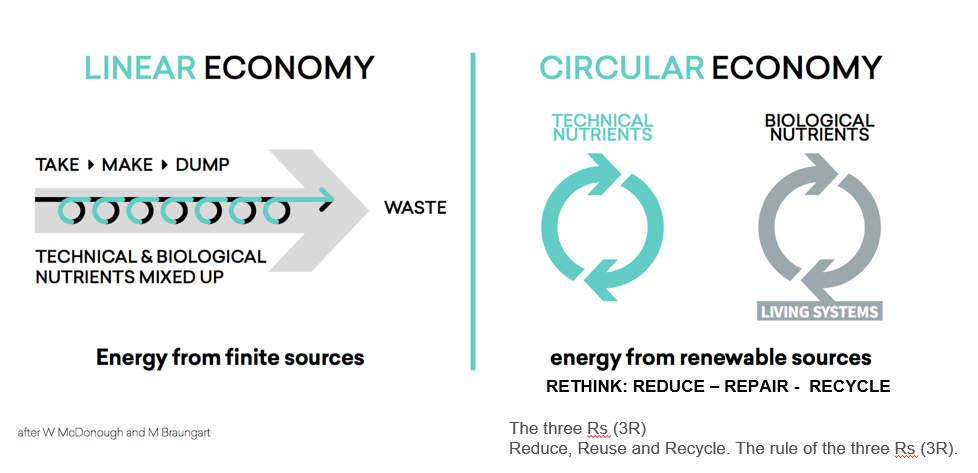

Circular economies are a way of reducing waste while maintaining production. While many products are designed to be used and disposed of, this involves making products and services that people can reuse in future items or allow nature to break down. This means instead of consuming resources from nature, waste is reused instead. However, this depends on people being able to afford and access sustainable options.

Benefits of Circular Economies

If products can last longer and are easier to repair, people will be more likely to keep their old goods-meaning less waste and fewer resources consumed. In addition, this can do more than ease our material footprint. The circular economy is a $4.5 trillion opportunity that can help our nations’ economies through new industries and jobs. In fact, every 10,000 tonnes of recycled waste can create up to 9.2 full-time positions, compared to 2.8 roles for the same amount of landfill.

In addition, less consumption can often produce more money. This is because most profits come from a small number of customers. Producing more also tends to cause greater marketing and operating costs. Studies have shown that many strive to buy less, meaning that producing more than people need can mean more unsold items. By only producing enough to meet people’s needs, businesses can gain more money through new opportunities, such as servicing and maintenance. Stopping overconsumption does more than save our Earth; it makes better lives for us all.

Conclusion

We consume more than the Earth can recover. Despite this, we waste much of what we gather. While many seek to gather more products, others cannot afford basic necessities. There are opportunities to do more with less, not only through changing behaviour but also by rethinking how we produce goods. To achieve this, citizens, businesses and governments must work together to not just want to consume less, but take action.

If we reduce overconsumption, we will use fewer resources, and leave less waste. This means we can not only heal our planet, but also create jobs and economic growth. To achieve this, we need to know where we stand, and how our actions affect our future.

The THRIVE Project framework lets citizens and businesses track their impacts, and understand how changes can improve our planet. It allows people around the globe to understand what can help us not just survive, but thrive!

If you would like to plant the seeds of change, click this link to find out more about our THRIVE platform.