A lot has been said about sea-spiracy or is it seas-piracy? This article addresses some key concepts which may help us differentiate between the hype and reality. After viewing the program on Netflix with a fellow colleague, discussing the program, and reading several reviews, it is clear we have a divided reception to this documentary.

As an expert in the science of sustainability, I was asked to comment. Rather than adding to the divide, I offer this simple and hopefully insightful commentary. There is truth in everything showcased in the documentary. To what extent ought it deride our understanding, raise fruitful discussion, answer questions, and most importantly inform our future decisions and actions, This is really where the debate ought to lie.

To add some substance to the discussion I would recommend looking at established scientific studies on the topic. For this, I would draw your attention to the concept of keystone actors (Osterblom et al. 2015), systems thinking (Williams et al. 2017), and context-based measurement (Haffar & Searcy 2018). Let’s delve into each individually.

What is a keystone actor?

Within many domains, there is the concept that a large percentage of the impact is derived from a small number of entities (actors) operating in the field. For example, in the seafood industry, the top 30 producers represent the vast majority of the labeled products we see on our supermarket shelves. By examining the actions of these international keystone actors, we can gain a clear understanding of their true impact on the world we live in. From farming through to the live catch, culling, storage, refrigeration, transportation, and various other logistics, until it eventually ends up in a market or tin can and then onto a plate.

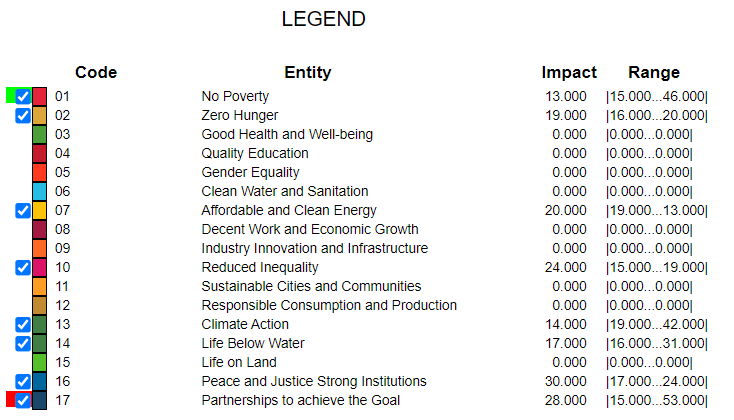

A study by THRIVE Project in 2019 (Fedeli 2019), explored in detail the impact of keystone actors on the seafood industry. It calculates and ranks the impact of organizations across a range of 60 material topics including strategy, reporting, disclosure, freshwater, GHG, food waste, use of plastics, endangered species, collaboration, aquaculture feed, bycatch, science-based management plans, disease, prevention and mitigation, workers rights, no discrimination, a living wage, gender-based violence, gender balance, recruitment, remedy, safety, rights, and building up of the local area.

The study concords with the World Benchmarking Alliance by identifying the key issues affecting the impact of organizations in their sector but then goes a step further by transparently showing the impacts of each of the material topics in reference to thresholds and allocation, and lower and outer limits. This is done at each successive scale-linked level (Fedeli & Glinik 2021), demonstrating the impact of sectors, regions, cities, countries, and indeed across the whole planet.

Why Systems thinking is important?

Systems thinking deals with the dynamic interactions within and across interconnected systems. Sustainability by its very nature is a systems-based concept, requiring an understanding of how one part integrates with and affects the whole. Systems thinking is a school of thought that recognizes that the whole is more than the mere sum of its parts. The interactions between the various elements are also extremely important. Is a working car a mere collection of components? There is a quality that is derived specifically from how components come together which makes it a functional (or indeed dysfunctional) system.

Upon taking this holistic view we soon realize that impact on our planet cannot be ascribed in mere isolation. It is also essential to take stock of each of the capitals we have on hand. These fall into categories such as natural, social, financial, man-made, and intellectual (diagram). Although for centuries accounting and economics have been known for aggregating these through monetization (Pearce 1998), the reality is that this is not how societies nor environments work.

For example, stranded in the desert with an ingot of gold in my back pocket, is not going to ensure my survival. The concept of ensuring that resources are not being aggregated and offset by another is described as taking a strong sustainability stance (Upward & Jones 2015, Bjørn & Røpke 2018). This ‘law’ of non-substitution is essential to ensure systems thinking is being applied when evaluating sustainability impact claims.

Enter context-based measurement

This leads us to the next major issue of context. When we say context-based metrics, we mean to ensure a resource is used within the specific allowances afforded by said resource. For example, a watershed that produces 100,000 liters of water a day, servicing a neighborhood of 100,000 households, means on average a liter per household a day. Whilst this is not the only way to allocate use, we will use this example for simplicity. Now if households in a street started to routinely use more than their fair share, like say 2 liters a day, then at some point, some households will be met with no water when they turn their tap on, and thus some households will go thirsty.

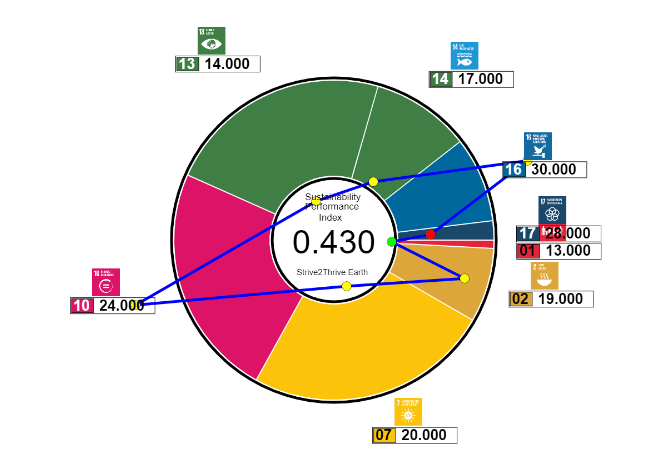

This boils down to fair share, ensuring resource use is within the resource allowance, within acceptable thresholds and allocations. Thresholds are usually depicted as a range. In general, when discussing sustainability we refer to social floors and environmental ceilings. This can be more easily visualized and explained with a diagram such as the ciambella chart (see figure below). We say that an entity’s impact is within an acceptable range when it is between the lower and higher range of the scale. The more sustainable, the closer it is to a perfect score. This is the essence of context-based impact assessment. Measuring impact within the norm of the acceptable range, outside of which the system is unable to cope and essentially breaks down. Performances outside of the normal range (the coloured region in the chart) are unsustainable.

CIAMBELLA CHART

(THRIVE Platform: https://platform.strive2thrive.earth)

Ultimately all resources on planet Earth are limited. We have only one planet and a fixed or finite amount of natural resources such as fertile soil, minerals, and freshwater supply able to sustain crop production and sustain all living creatures. Whilst some resources are regenerative (such as plants and life-forms), there are fundamental rates of attrition we need to contend with. Resilience to threats and the ability to regenerate is another yet subject in its own right and usually tackled within the ambit of the circular economy.

What is the controversy surrounding Seaspiracy?

Bringing it all together. The review conducted by THRIVE Project using the free online THRIVE Platform tool demonstrated the sustainability performance of the top organizations in the seafood industry. In doing so it considered:

- keystone actors and scale-linking

- systems thinking and strong sustainability

- context-based measurement and finite resources

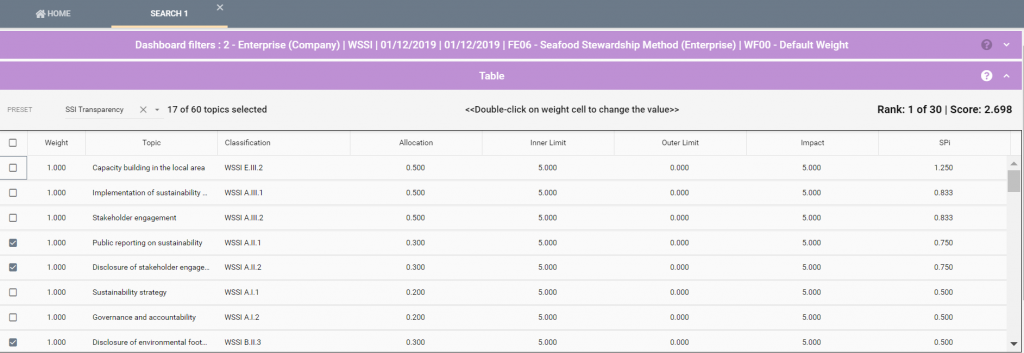

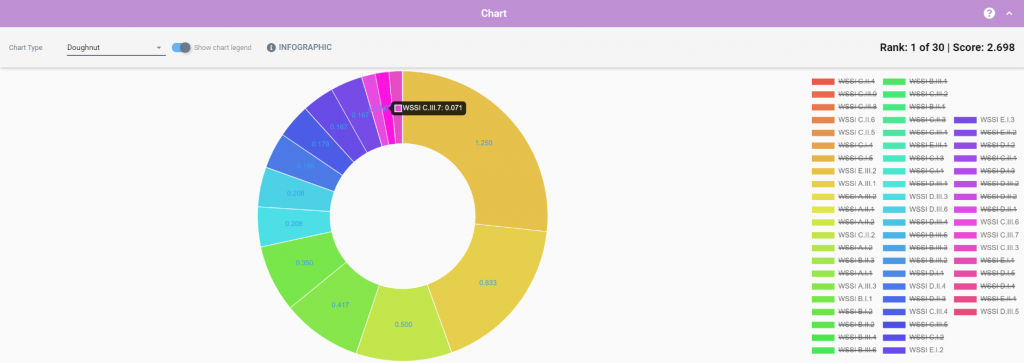

The top performer, with a score of 2.698 out of 5 was found to be the Thai Union. We use the WBA SSI scale here as this provides a ready reckoner for anyone wishing to compare with findings elsewhere (WBA SSI). Thai Union represents a number of quite familiar labels such as Red Lobster and John West. A list of some of its specific impacts within context can be found in the table below. Full details available free from the THRIVE Platform website. The findings also show the associated business model of the organization in question which allows one to link performance to strategy. For more on this see Sustainable Business Models.

Thus, to really understand the impacts of an entity, such as an organization, requires a fair bit of a study of the charts above. Across specific topics, one can see the impact of each and ascertain whether this impact is favourable or not and needs improving. One cannot simple aggregate the impacts and utilize and overall score as the be all and end all of comparison. Hence the need for an extensive interactive open and transparent tool such as the THRIVE Platform.

Conclusion

The show was surely looking for publicity and hence possibly pursued sensationalism in favour of normative reporting in some areas. However, it is fair to say that this program highlighted a number of unsustainable and downright harmful practices. No 90min show could ever do justice to the subject. For example, why harm the whales? How are multinationals getting away with labeling products as sustainable even if there is no basis or justification for claiming so? Furthermore, the show exposed slave labour practices and failed to include the ecosystem in its (systems) thinking. After all greenwashing is alive and well, the last time I looked. Make a point to know your facts instead.

Those interested in delving deeper are urged to check out the above at the THRIVE Project Platform website. It quantitatively shows how companies are performing relative to their peers and to the industry. Do visit and register for free online at the THRIVE platform and/or watch this educational video explaining how it works.