What does the term ‘social exclusion’ really mean? How does it reflect the level of poverty in a society? Some researchers see a direct connection between the two concepts. Many also suggest that poverty falls under the social exclusion ‘umbrella’.

In fact, the concept of social exclusion originates from France in the 1970s. Here, the socially ‘excluded’ were disabled people, single parents, and the unemployed who had no social insurance protection. Their lack of participation in society, and perhaps their ‘invisibility’, rendered them excluded from it.

We look at the different definitions of social exclusion and poverty, and how the language of exclusion (or deprivation) is useful in understanding the enduring challenges of inequality.

A New Definition of Poverty

After the 1970s and the impacts of stagflation, many more people found themselves excluded from mainstream society. Also, the definition of social exclusion broadened. For example, it began to include people with mental health issues, and immigrants, as well as those suffering under long term ‘poverty’ (Buckmaster & Thomas, 2009; Rawal, 2008).

In the 1980s, as unemployment continued to rise, national movements for justice emerged in France. Thereafter, a more comprehensive approach to the study of social exclusion was developed (Buckmaster & Thomas, 2009). In 1979, Peter Townsend published his major study on poverty in Britain. He sought to redefine it as a condition of ‘relative deprivation‘:

“Rather than defining poverty, as earlier studies and official policy had done, in terms of levels of income necessary for subsistence, Townsend argued that the crucial issue was whether people had sufficient resources to participate in the customary life of society and to fulfil what was expected of them as members of it.”

Levitas, 2005

The Language of Social Exclusion and Poverty in Europe

Economic hardship and higher rates of unemployment in Europe led to the creation of new theoretical frameworks, as well as attempts to redefine old concepts like Townsend’s analysis of modern poverty.

So, by the late 1980s, the European Union had adopted the concept of ‘social exclusion’ as a unified political concept. It quickly became an established term in social policy, replacing the concept of poverty (Rawal, 2008).

Yet, some experts argued “that the concept of social exclusion is no more unambiguous than the concept of poverty” (Rawal, 2008). Still, the term ‘social exclusion’ frequently appeared in their articles. Then, as the term became popularised in other countries, it adapted to different political agendas. The socially excluded came to include new cohorts, refugees for example. These kinds of adaptations led to the concept taking on quite different meanings from the original French. Thus, definitions of social exclusion and poverty were as variable as the situations they were describing (Rawal, 2008).

What Causes social exclusion?

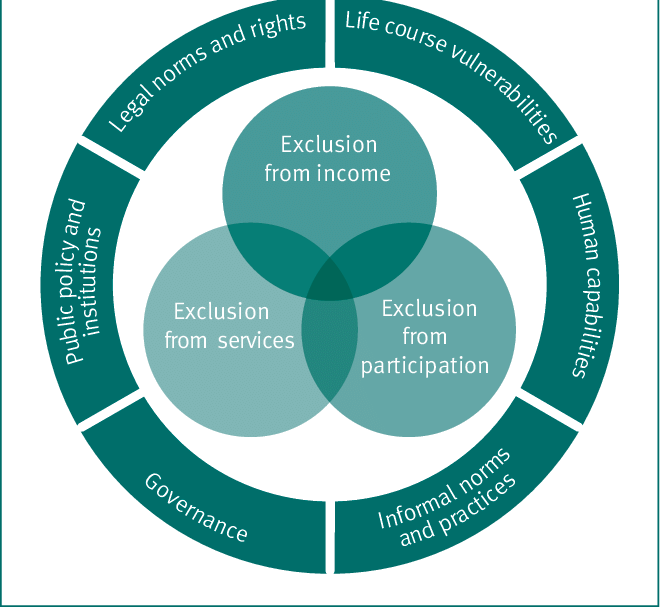

Now, social exclusion encompasses all the restrictions to a full participation in economic, political, and cultural life. Thus, it typically affects those outside the ‘mainstream’ of society. For example, those who do not have the same opportunity to have their voices heard as others. Equally, it applies to people who do not have access to ‘basic necessities’ like running water or electricity.

According to Giddens (2009), the social forces which shape people’s circumstances are also important in a discussion of social exclusion. Social forces can, for instance, become agents of exclusion during a pandemic or other catastrophe. In those situations, the individual’s social influence has a profound effect on their circumstances (Rehnberg, 2021).

For Levitas, the concept of social exclusion represents a division between an included majority and an excluded minority. This, she argues, applies to most of the theoretical frameworks on the subject. For example, it applies in any discussion of poverty, gender, sexuality, ability, literacy, age, or race. In fact, there are no limits to what we may take exclusion to mean. It may be said to apply to any group having difficulty achieving the same rights as the majority.

Nonetheless, social researchers insist that analytical clarity is essential precisely because it is such a broad concept (Levitas, 2005; Rehnberg, 2021).

Social Inclusion

On the other hand, the term social inclusion refers to government and community policy designed to improve participation in society. In particular, it describes those policies intended to help those who are suffering from social exclusion.

Therefore, inclusive policy enhances opportunities for those who are disadvantaged according to age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, religion or economic status. It allows those groups to access resources otherwise denied them, and it provides them with a ‘voice’ to the society as a whole.

However, social inclusion is not the direct opposite of social exclusion. It, too, has many definitions. Thus, the institution, region, or country in which it appears has a profound effect on how and where it is applied.

Theories of inclusion have also been subject to criticism. Rawal (2008), argues that literature which conceptualises exclusion usually tends to have a very simplistic concept of inclusion. Rather, the two concepts should be seen to be in a symbiotic relationship, or as “inseparable sides of the same coin”.

The conceptual failure, he argues, stems from an inability to “develop a critical understanding of the real and discursive geographies of social inclusion” (Rawal, 2008). Again, the different understandings of both social exclusion and inclusion make it difficult to develop a comprehensive definition. The UN has provided guidelines, but these are not definitive.

Social Forces as Agents of Exclusion: An Australian Example

Border closures during the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the number of flights to Australia. This led to greatly increased ticket prices, on top of mandatory hotel quarantine paid from the returning citizens’ own pocket.

Many Australians felt socially excluded as a result of this experience. A large number had lost their foreign jobs and, lacking a social network overseas, wanted to move back to their home country.

However, due to the reduced flights and increased prices many had trouble returning, especially those who were not well off to begin with.

This is a concrete example of how stratification within the citizenry can create hardships that lead to a sense of exclusion and reduced access.

“Unemployment is challenging for those who have worked in a low-income position, as it may have been difficult for them to accumulate savings to support themselves in-between employment… Results suggest that, aside from financial and social constraints due to COVID-19, there have been factors of exclusion towards Australian citizens living in Finland due to the border closures in Australia. These restrictions have left the citizens incomplete as they have not had the same rights as those within Australia.”

(Rehnberg, 2021)

Social Discrimination and Social Justice

There are two related concepts that provide guidance on inclusion. In particular, the principles of social discrimination and social justice. Both principles may provide the basis for social policies.

“Social discrimination is defined as sustained inequality between individuals based on illness, disability, religion, sexual orientation, or any other measures of diversity.”

(Bhugra, 2016).

A just and equitable society asserts that each individual is born with the right to dignity and equality. Physical illness, age, gender, or other differences, should not render anyone more vulnerable than another. Social discrimination can be said to occur when one part of society suffers behaviour that is damaging, derogatory, and demeaning. The end result is turning certain people into second-class citizens.

“Social discrimination appears to be lodged in the system and, therefore, can be pervasive and intrusive, and stop people from reaching their full potential and, more importantly, labelling them changes their identities. Micro-identities related to race, gender, age, religion, sexual orientation, and other components all get trumped by the label of being mentally ill.”

UNESCO,1968

Social Justice

Social justice, therefore, is where the values of diversity and equal opportunity may be said to apply to all. These values are enforced regardless of ethnicity, gender, age, disability or economic status. It also implies an acceptance of all sexual orientations, religions, beliefs, and a sense of basic human rights when it comes to the allocation of resources. Thus, a ‘just’ society condemns all discriminatory behaviour and ensures that basic human needs like food, clean water and sanitation, are met.

“The notion of equal rights, a foundation of social justice, is an important part of the international discourse and is probably gaining ground overall, at least in the global consciousness. Many groups that have traditionally suffered discrimination now have some hope of enjoying equal rights. The considerable progress made towards achieving gender equality has been mentioned repeatedly.”

United Nations, 2006

Social justice may well be considered to be an organising principle of society. The ‘Forms of Moderation’ used by English philosopher, David Hume, may be helpful in this regard. Justice is, after all, about the common good, and this applies not only to communities and organisations, but to future generations:

“Moderation is probably useful in protecting the environment and can therefore contribute to the achievement of justice for future generations.”

(United Nations, 2006).

Social exclusion and Poverty: The Nepalese experience

In 2003, the government of Nepal incorporated ‘inclusion’ as a pillar of its Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) (Rawal, 2008).

The state created public discourse on such themes as inclusion, state restructuring and proportionate representations. However, according to Nabin Rawal, there is no doubt that minority groups have had their rights denied, especially in terms of cultural and linguistic expression.

This kind of public discourse, he argues, is a front for inaction. Inclusive policies may get discussed but no attempt is being made to implement them. Part of the problem is perhaps the use of generic ’buzzwords’ rather than a focus on specific challenges.

Instead, he argues, variations of privilege should be identified within each social subcategory of Nepalese society. These should also include variations of privilege within each caste and ethnic group. Debating these ‘identities’, Rawal says, will provide an opportunity for issues of inclusion and exclusion to be addressed.

The experience of Nepal demonstrates that each country or community has specific issues relating to social exclusion and the ways to improve social inclusion. Therefore, a comprehensive definition of ‘social exclusion’ is perhaps not useful, or even possible, for every circumstance.

Does Social Exclusion Cause Poverty?

Social exclusion can, however, be a useful way to show how people’s citizenship status affects poverty levels in a society. Social exclusion examines how inequalities in the exercise of individual and collective rights influences the development of a class, or caste-based, society.

More broadly, this is a discussion about political deprivation. There is a strong causal relationship between political deprivation and poverty. Social groups with the highest degree of exclusion are also the poorest. So, forms of social segregation like castes and classes tend to reflect the concentrations of poverty and inequality in that society (Gore, 1995).

Poverty is multi-dimensional

“Social exclusion matters because it denies some people the same rights and opportunities as are afforded to others in their society. Simply because of who they are, certain groups cannot fulfil their potential, nor can they participate equally in society. An estimated 891 million people in the world experience discrimination on the basis of their ethnic, linguistic or religious identities alone.”

DFID, 2005

However, is poverty a cause, or the consequence, of social exclusion?

There is no simple answer. Poverty is multidimensional. Unequal opportunities allow some groups to thrive whilst others suffer deprivation in income, literacy, nutrition, and experience higher mortality, and morbidity. ‘Deprived’ groups are also often denied basics like water and sanitation, and experience greater vulnerability to economic shocks overall.

‘Poverty’ itself thereby leads to social exclusion. Affected groups are poor in terms of income, health, and education. This also has an emotional dimension, as those that are denied access to services have lower expectations in life. They effectively become closed out from their society and the opportunities it provides (DFID, 2005).

This directly affects the degree of capability, energy, and opportunity that socially excluded people have to increase their income and escape from poverty on their own.

Thus, even when an economy is growing and incomes are rising, ‘socially excluded’ groups may still be left behind. In addition, poverty reduction measures often fail to reach them. For example, people with disabilities, pensioners and refugees who are excluded from mainstream society may simply not be equipped to make use of such measures.

Universal Basic Income

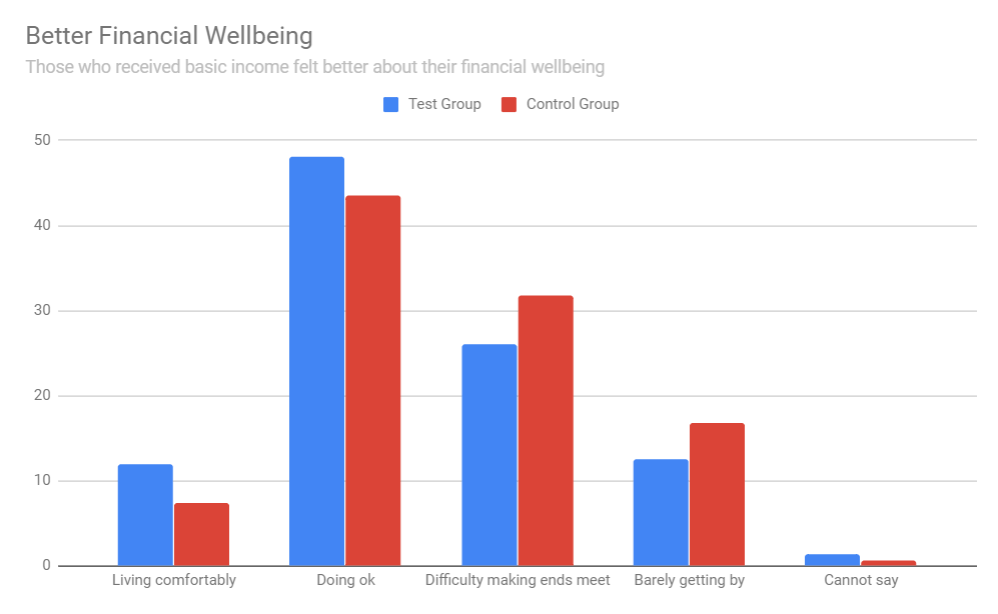

A solution might be in innovations like the universal basic income (UBI). A UBI is a policy principle in which all citizens receive a regular and equal financial grant from the government without a means test. This guarantees a minimum income and thereby allows everyone some degree of financial freedom.

In Finland, a recent two-year experiment in UBI improved well-being by producing better health outcomes and lowering stress levels, depression, and loneliness.

Another benefit of the UBI is that it provides individuals with sufficient access to basic necessities so that they may devote more time to entrepreneurial or other investments. This gives socially excluded people, in particular, greater freedom to escape the poverty trap.

Social Exclusion and Poverty: An Impediment to Sustainability?

The aim of the UN’s Sustainability Development Goal (SDG) 1 is to end poverty by all means. This has been somewhat successful in that poverty has declined over recent decades. However, COVID-19 has disrupted poverty elevation programs all over the world.

New research published by the UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research warns that the economic fallout from the global pandemic could increase global poverty by as much as half a billion people, or 8% of the total human population (United Nations, 2022).

Further, employment alone does not guarantee a decent standard of living. Much depends on the category of job and the marketplace for skills. Worldwide, the poverty rate in rural areas is 17.2 per cent. That is more than three times higher than in urban areas (United Nations, 2022).

Social protection is the most effective way to reduce the risk of poverty. However, following the devastation of Covid-19, many social insurance programs have been downgraded.

Undernourishment is a major theme of SDG 2 (No Hunger). Yet, current estimates show that nearly 690 million people, or 8.9 percent of the world population, are hungry. That amount has risen by 10 million people in one year, and by nearly 60 million in five years (United Nations, 2022).

According to the World Food Programme, 135 million suffer from acute hunger largely due to man-made conflicts, climate change and economic downturns (United Nations, 2022).

Interconnected Goals

The relationship between eliminating poverty and other sustainability development goals is far reaching and complex. The UN’s Agenda 2030 regards all 17 Sustainability Goals as interconnected. Therefore, the ability to achieve emissions goals and climate change reduction measures is greatly dependent on the success of goals that seek to reduce hunger, poverty and inequality worldwide.

It is for this reason that progress on social exclusion remains an imperative, despite the challenges of recent years. With war, refugees, and a global pandemic, the challenge to meet SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 2 (No Hunger) has never been greater. However, the dire need to address Climate Change and achieve Net Zero makes their success essential.

Conclusion:

Social exclusion and poverty are two concepts that defy comprehensive definition but, in general, they describe the degree of participation and equity within a given society. Different institutions and governments have their own theoretical frameworks for describing the particular challenges, objectives and outcomes they must address.

However, the fact remains that the complexity of global progress towards sustainability depends upon the elimination of poverty and world hunger. There is no sustainable society in an unsustainable world.

The Thrive Framework: Progress Towards Sustainability

“Much like a stethoscope, the THRIVE Platform tool keeps track of the well-being of each entity, measuring their impact on the vital capitals of the planet.”

Morris Fedeli, The Thrive Project

At its core, sustainability simply means the ability of the planet to continue, to survive. ‘Thrivability‘, by contrast, is the next step, beyond sustainability. THRIVE believes that humanity can do better with the knowledge currently available to us. We want to instil the idea that sustainable solutions not only prevent disaster, but offer the potential for societies that flourish.

The THRIVE Framework examines issues and evaluates potential solutions in relation to this overarching goal of thrivability. It is about making predictive analyses using modern technology that support environmental and social sustainability transformations.

This allows organisations to assess their sustainability performance in relation to strategy and provides guidance for future transformations beyond sustainability. Measuring the sustainable dimension of business models is critical in the modern era. To continue generating value from the environment, an organisation must calculate its effects on that environment (Evans et al. 2009).

The Thrive Framework emphasises an holistic approach which is value oriented and integrates innovation for prosperity.

To learn more about how The THRIVE Project is researching, educating and advocating for a future beyond sustainability, visit our website. You can follow our informative blog and podcast series, as well as find out about our regular live webinars featuring expert guests in the field. Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates.

GOT A QUESTION ON THIS TOPIC?