The activist and academic, Carl Oglesby, first used the term, ‘The Global South’, in 1969. He used it to refer to a group of countries that remained poor in relation to the wealthy Western and European powers long after the end of colonialism.

Today, the term is increasingly popular. Globalisation and the climate crisis are high on the international agenda. ‘The Global South’ is both geopolitical shorthand and a movement for change.

In this article we’ll discuss the origins of the push for global equity. We’ll also look at how the world has embraced the cause in its pursuit of sustainability.

The Impact of Imperialism on the Global South

In the 1920’s a group of ‘post-colonial’ leaders gathered to discuss their plight. They felt that the exploitation of countries in the African continent, South America, the Middle East, and much of Asia had financed industrialisation. Rich countries had become rich from resource extraction, forced labour, genocide and theft.

The group would not meet again until 1955, at the Bandung Conference in Indonesia. Post war politics was, by then, focussed on the cold war between East and West. Poor nations were now known as the ‘Third World‘.

Still, the Non-Aligned Movement continued to point to the persistent problems faced by certain countries. Many of those did not enjoy the benefits of global capitalism. Many seemed to be exploited by it.

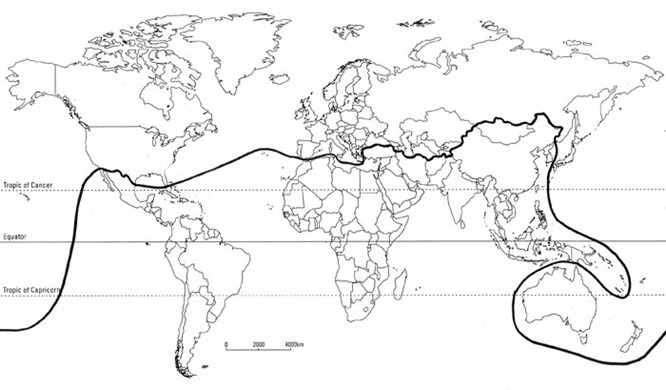

The Southern Line

The idea of a third, or ‘developing‘, group of nations holds until at least the end of the 20th century. The ‘Brandt line’ from the 1980’s illustrates the thinking of the time, a divide between wealthy ‘Northern’ countries and their Southern neighbours. Divisions of this kind, however, become less relevant in the years that follow.

By the turn of the millennium, the Global South begins to appear more often in research papers. Here, it conveys the wealth gap both within and between nations. It also suggests a new, collective drive for justice.

At front of mind was the rising ecological threat. Exploitation appeared to have had a social, but also a major environmental, cost. As a result, issues of global equity were moved right to the top of the agenda.

The Global South today describes “not only systemic inequalities stemming from the ‘colonial encounter’…but also the potential for alternative sources of power and knowledge.” (Haug et al).

So, Why Does Inequality Persist Under Capitalism?

There are many theories why some countries do not enjoy the success of rich nations. As ‘Systemic Inequality’ suggests, problems in the relationship can limit the ability of poor countries to grow.

Dependency Theory

‘Dependency Theory’ argues that capitalism sets up resources to flow from under-developed countries to wealthier ones. Guatemala, for example, lacked the knowledge and industrial base to make new products, and had only its natural forests to export. The resultant over-foresting and environmental damage worsening that country’s relative poverty.

Or, poor countries become deeply indebted, like the billions loaned to African countries from the 1970’s. By early this century the compound interest had become a crushing burden on their national economies.

Poorer nations might then make unsustainable investments to meet repayments. This can enrich a small entrepreneurial class, but the average person struggles to survive. The end result may be political instability and violence, and a failing economy.

Digital Colonialism and the Global South

‘Information dependency’ says that developing economies suffer from the digital divide. They’re generally the last to hear about new technologies or enjoy the business opportunities created by them.

Also, monopoly power transfers wealth via rent and surveillance. Tech companies like Microsoft, Apple, Google and Facebook profit from most digital experiences because they control the ecosystem. However, they also retain valuable data from each transaction, further increasing their power.

“Like the railroads of colonial empires, US multinationals have consolidated control over the structural components of the digital ecosystem, which has been engineered for ruling class dominance over social, political and economic life.”

(Kweet, Michael, ‘Break the Hold of Digital Colonialism’, Mail and Guardian, June 2018)

Uber, for example, takes up to 25% from each ride. It sends the proceeds directly to the US. However, the company also retains a massive trove of free customer data for future applications. This recalls Clive Humby’s comment from 2006 in which he labels data ‘the new oil’.

‘Natural’ Accumulation

Another theory says that concentration of wealth is simply a natural gathering of industry. Capital collects in places where it’s already most active and supported by local infrastructure. This, in turn, affects future investments.

Also, the existing work culture and skills base of the local workforce plays a big part. An unstable or under-resourced workforce is simply less attractive to investors, even if it is much cheaper.

Unsustainable Development

Unsustainable or ‘dirty’ development can impose massive social costs (air, soil and water quality, building and work safety, for example) that puts communities at a severe disadvantage. Workers living in unsafe dwellings and made ill by pollutants and disease are hardly reliable or competitive.

International Efforts to assist The Global South

The challenge of creating growth, as well as global equity, is finding a way to build sustainable societies everywhere. Environmental and population pressures, resilience to natural disasters and the protection of human rights are important markers of progress.

International development goals were first proposed in 1996 by the United Nations. They would seek to cut poverty by half, make primary education available to all, and greatly reduce infant and maternal mortalities by 2015.

The Millenium Development Goals

In 2000 these aspirations were ratified by the UN into 8 broad Millenium Development Goals (MDG’s):

- eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- achieve universal primary education

- promote gender equality and empower women

- reduce child mortality

- improve maternal health

- combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

- ensure environmental sustainability

- develop a global partnership for development

Kofi Annan framed the future role of the UN: “to ensure that globalisation becomes a positive force for all the world’s people, instead of leaving billions of them behind in squalor.”

With this statement, the UN acknowledged the interdependence of the world’s economies. Unfettered global capitalism no longer seemed to be the solution to vast inequalities and the existential threat of climate change.

Mixed Success

The MDG’s followed three key principles for improving living standards (social, economic and political):

- Human capital

- Infrastructure, and

- Human rights

Aid from developed economies actually rose over the lifetime of the MDG’s. However, more than half went towards debt relief. Natural disasters or military aid took up much of the rest.

Also, the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 slowed efforts to ramp up programs closer to the deadline. By 2012, most donor countries had fallen below the target giving rate of 0.7% of Gross National Income. (Speri, Alice, Where’s the Money? Funds for Millennium Goals Lag, Pass Blue, 2013)

The MDG’s also suffered issues of accountability and corruption at a national level.

However, of the 18 measurable targets formulated from the 8 MDG’s, there was great success in halving the number of people living in extreme poverty, as well as improving access to safe drinking water. There were also big gains in gender parity and access to education, as well as reductions in diseases like malaria, measles and TB.

There were clear failures too, most notably in attempts to reverse the loss of environmental resources and biodiversity.

Overall, the MDG’s made inroads against hunger and poverty. Yet, according to UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon, “for all the remarkable gains, I am keenly aware that inequalities persist and that progress has been uneven.” (Were the Millenium Development Goals a Success? World Vision, July, 2015)

The New Sustainable Development Goals

The UN learned from all the work put into the MDG’s. In 2015, 17 new and interlinked goals promised ‘a more sustainable future for all’ by 2030.

China’s economy had grown steeply in the last two decades and the climate emergency had become critical. It followed, then, that the SDG’s were broader in their scope and more ambitious, and recognised the close relationship of each goal to the others.

SDG’s (2015)

- No Poverty

- Zero Hunger

- Good Health and Well-being

- Quality Education

- Gender Equality

- Clean Water and Sanitation

- Affordable and Clean Energy

- Decent Work and Economic Growth

- Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

- Reduced Inequality

- Sustainable Cities and Communities

- Responsible Consumption and Production

- Climate Action

- Life Below Water

- Life on Land

- Peace and Justice Strong Institutions

- Partnerships to achieve the Goal

Will There Still Be a Global South?

Sadly, communities from what we call ‘The Global South’ still very much rely on help from rich governments. Today, with global warming and sea levels rising, this is often a matter of sheer survival.

Countries like Uganda, for example, which produces very little in the way of emissions, are nonetheless suffering the most devastating effects of climate change on food production and household income. Others, like low lying island states in the Maldives and the Marshall Islands, are dangerously threatened by coastal erosion.

The SDG’s focus on the protection of the planet and its natural resources. However, they also recognise that global sustainability hinges on sustainable societies.

Peaceful, just and inclusive communities, safe and affordable housing, safe and effective transport systems and workplaces, and the protection of natural and cultural heritage are all essential parts of the same project. Without fundamental change we are all living in an unsustainable world.

Thus, the way forward for the Global South means sustainable societies everywhere, regardless of geography.

To learn more about the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals sign up for our monthly newsletter or visit the website. THRIVE produces a blog, as well as regular podcasts and regular webinars on related topics. We are always on the look out for contributors.