From iced coffee straws to takeout bags, plastic has become a daily necessity. Many fields use plastic, such as aerospace, construction, packing, energy generation, and others. However, of the 6.3 billion metric tons of plastic waste made, studies have shown that only 9% of this was recycled. This means the other 91% pollutes our landfills and oceans. New technologies and methods, however, may allow us to transform plastic so it doesn’t pollute our ecosystems.

Dealing With Plastic Waste

Scientific knowledge is opening up new ways of dealing with plastic waste. Microbiology, for instance, uses microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi to break down plastic. Synthetic biology and directed evolution, focused on modifying substances to break down plastic faster. Enzymes, proteins that help speed up chemical reactions, play a large part in this.

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is a plastic material common in food packaging and household items. Enzymes designed to break this down have seen major developments in recent years. PET is only reusable once, as traces of metal from manufacturing weakens it over time. Therefore, it is often reused in less demanding applications such as carpets, fiberfill for coats and sleeping backs. Another way is to use them for metal-organic frameworks, suited for gas storage and separation.

Transforming Plastic into Vanillin

However, it’s possible to create vanillin from PET waste. This is more than a flavouring agent in food products (think vanilla). It also acts as a fragrance in a wide variety of industries. These include cosmetics, medicines, herbicides, and others. In 2018, vanillin demand went over 37,000 tons globally. This is projected to increase to 59,000 tons (with a revenue forecast of $734,000,000) by 2025.

While vanillin naturally comes from vanilla beans, there are not enough of these to meet demand. Therefore, fossil fuel chemicals make up most of the world’s vanillin. A recent study shows how terephthalate (a chemical in PET) can make vanillin instead. This could make it easier to meet vanillin demand and reduce plastic waste.

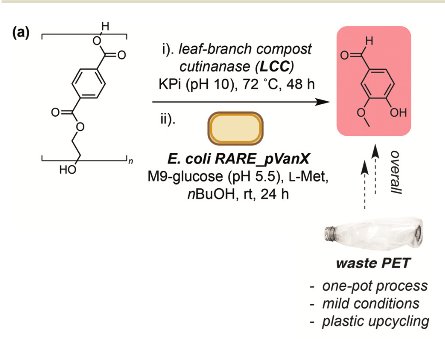

In the study, water molecules broke down PET by starting a chemical reaction with a heat-resistant enzyme called LCC WCCG, to release terephthalate. This took place at a temperature of 72 degrees Celsius, with the enzyme at its semi-purified form. Once the reaction cooled down to room temperature, they added E. coli RARE_pVanX cell structures, and a mixture that enhances DNA uptake to the reaction. This would be analyzed for 24 hours. The microorganism E. coli would transform the broken down PET into vanillin.

Thus, the study shows a way to transform plastic into vanillin. This can not only allow producers to meet the increasing demand for vanillin, but also reduce plastic waste. It has the potential to help the economy and the environment.

Vanillin and its Applications

Vanilla is a widely-used flavouring substance. However, according to Walton, Mayer and Narbad (2003), “[a]lthough more than 12,000 tons of vanillin is produced each year, less than 1% of this is natural vanillin from Vanilla [plants]”. Therefore, synthetic vanillin is in more demand than ever. However, there are other reasons as well. Synthetic vanillin is also much cheaper. The cost of vanillin from vanilla pods or beans ranges from $1200-$4000 per kilogram, compared to synthetic vanillin which regularly sells for under $15 per kilogram.

Many products use synthetic vanillin, including food, fragrances, and pharmaceuticals. Over half of all produced vanillin is used for pharmaceuticals alone. These include herbicides, anti-foaming agents, drugs, and antimicrobial agents, among others. Several non-food products have vanillin, such as household items, e.g., air fresheners and floor polishes. Due to its antimicrobial properties, vanillin also works as a food preservative.

Every year we throw enough plastic away to circle the earth 4 times.

Fun Fact

This is just the start. In the future, it may be possible to transform plastic into other food products, which should help us reduce waste and let us all thrive. For more information on how to sustainably use plastic, visit THRIVE Project.