Index

- What Is Sustainability Materiality?

- Sustainability Reporting

- Double Materiality

- Determining Sustainability Materiality

- Definitions Of Financial Materiality

- Linking Financial And Non-Financial Materiality

- Considering All Stakeholders In Determining Materiality

- Moving Forward

- Why Is It Essential To Focus On Sustainability Materiality?

- Achieving The United Nations’ Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs) And How They Link To Materiality

- A Thrivable Framework

Source: Unsplash

What Is Sustainability Materiality?

Materiality is the difference between a weak sustainability strategy and an approach that is well thought-out, planned, and based on importance (Tantram, 2019). Materiality, in simple terms, means what’s significant and relevant. The term is commonly used in the accounting and legal profession and is referenced in the context of impact on a business.

Materiality helps organisations focus on the most significant economic, environmental, and social issues affecting their business. As such, it plays a crucial role in sustainability reporting. Materiality is the principle that guides organisations in identifying and prioritising these non-financial topics that are most relevant and impactful to their operations and stakeholders (NYUStern, 2019).

Sustainability reporting

Sustainability reporting discloses a much broader set of information than just financial statements. It is becoming increasingly popular and required by new regulations. These sets of information need to be as reliable as financial information. For this to happen, sustainability reporting needs to be standardised. Users of such information should be able to make effective comparisons between the corporations reporting them. Another challenge linked to sustainability reporting is for businesses to determine which factors are most important in their impact on value creation (Chakravarty et al., 2022). This is where the concept of materiality comes into play.

The importance of materiality extends to integrated reporting. An integrated report combines traditional financial information and the material parts of a company’s sustainability report. This shows the relationships and dependencies between the different dimensions of performance (Eccles and Youmans, 2015).

Double Materiality

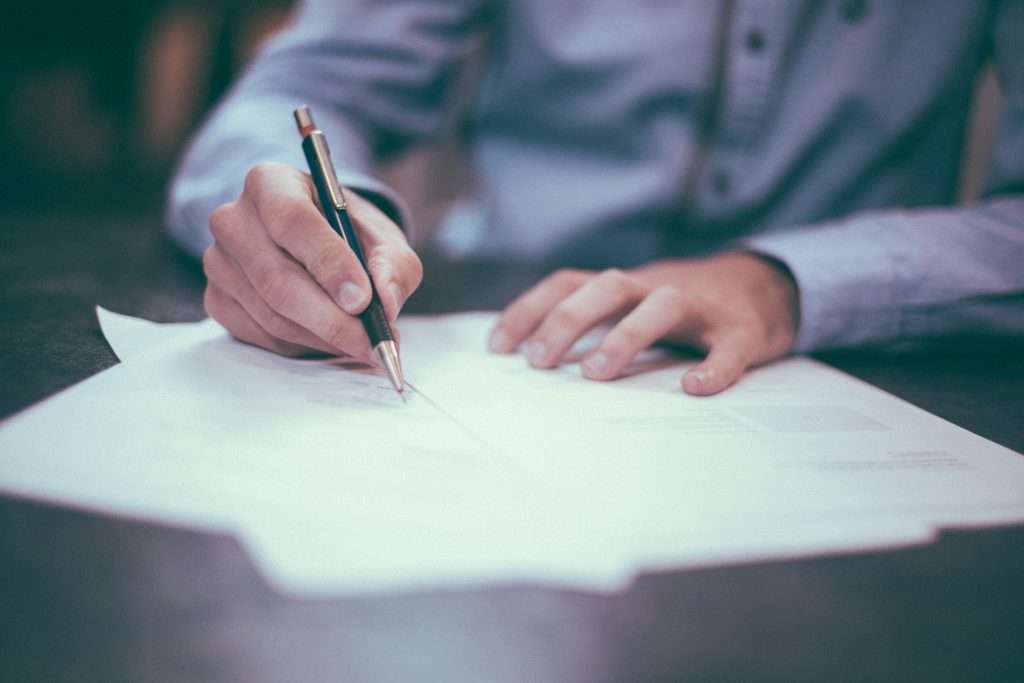

Source: GRI

There are two main directions of thinking about materiality: financial materiality and impact materiality. Together they make up the term ‘double materiality’ (GRI, 2022). Financial materiality is the impact of business activity on the shareholders, but impact materiality goes beyond that. It incorporates the impact on the economy, environment and people for the benefit of all stakeholders. According to the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), there has been much confusion with more terms introduced in addition to financial and impact materiality. These include dynamic materiality, nested materiality, extended materiality, and core materiality.

However, these terms are all based around and in between the two initial terms. Furthermore, it is well-accepted that any impact of an organisation will become financially material over time. Financial materiality and impact materiality together, then, coined under the umbrella term of ‘double materiality’, are the only relevant concepts of materiality. Both perspectives are needed in a two-pillar structure – for financial and sustainability reporting – with a core set of common disclosures and each pillar having equal prominence.

Triple Materiality

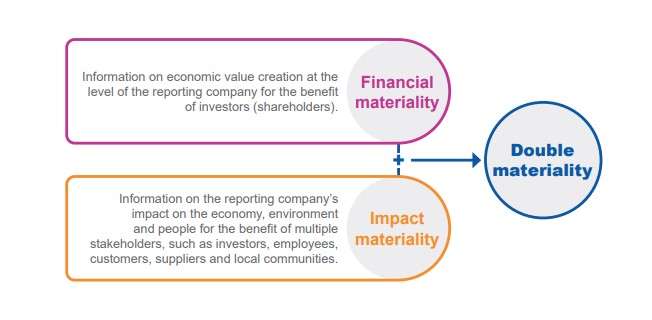

Source: THRIVE Publishing

Triple materiality is a concept progressing from double materiality to provide a more holistic framework for decision making and reporting. While double materiality takes into consideration the impact of organisations’ actions on the planet and society and vice versa, triple materiality adds the context of sustainability thresholds and allocations (Bill Baue, 2022). These allocations are based on planetary boundaries and scientific thresholds which are provided for at the individual organisation level (Hardyment, 2023). In other words, providing context to a topic to better understand its impact. For example, water and sanitation might matter in the supply chain of one product but may not matter for a different product in a different region.

Bill Baue draws on the connectedness of “Triple Materiality” and “Context-based Materiality”. He believes double materiality is simply insufficient to consider all impacts and risks involved in achieving sustainability.

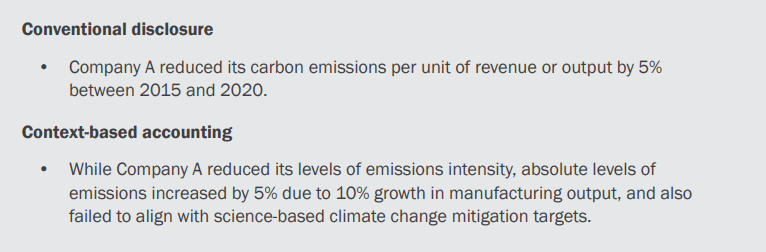

A good example of context-based disclosures in sustainability reporting is provided in the UNRISD ‘Authentic Sustainability Assessment’ manual, illustrated below:

Determining sustainability Materiality

At the current moment, there is no universally accepted or authoritative definition for ‘Materiality’. However, when it comes to non-financial information, they all revolve around a similar notion of being entity-specific, impacting value creation over the short or long term and taking into consideration all stakeholders (employees, customers, suppliers, communities), not just shareholders (Eccles et al., 2012).

Organisations have a moral duty to not only think about profits but also the benefit to society (internal and external). As part of this duty, it is important for organisations to report on their material impact to the environment and people beyond what is related to profit. In the end, materiality is determined by the organisation, and it is entity‐specific. While there may be no standardised conditions to follow in determining materiality, how companies go about making the ultimate decision of which issues are material for reporting purposes should be clearly explained as a defined process with solid lines of responsibility.

The concept of materiality in financial reporting has both quantitative and qualitative aspects. The financial industry uses a common numerical threshold. For example, 5% of earnings or 10% of total financial assets as a determination of materiality. Similarly, international organisations have published rules and regulations. Most of them are common in the fact that they provide general guidance and do not give specific numerical guidelines on how to determine materiality. However, they exist within clearly defined accounting standards and ultimately have the backing of laws.

definitions of financial Materiality

The following are the most important definitions of materiality for financial reporting:

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) – Information is material if omitting, misstating, or obscuring it could influence decisions that users make on the basis of the financial information of a specific reporting entity. In other words, materiality is entity-specific and relevant based on the nature or magnitude of the items to which the information relates in the context of an individual entity’s financial report. Consequently, the Board cannot specify a uniform quantitative threshold for materiality or predetermine what could be material in a particular situation.

- Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) – The significance of an item to the users of a listed corporation’s financial statements signifies materiality. A matter is “material” if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable person would consider it important.

- Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) – In interpreting the federal securities laws, the Supreme Court of the United States has opined that materiality must be decided on a case-by-case basis and has held that a fact is material if there is “a substantial likelihood that the …fact would have been viewed by the reasonable investor as having significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information made available.” As the Supreme Court has noted, determinations of materiality require “delicate assessments of the inferences a ‘reasonable shareholder’ would draw from a given set of facts and the significance of those inferences to him…”.

Between all these different bodies, the commonality is that they all share the view that materiality is entity-specific. Further, they all indicate that it should be considered significant to affect the decision-making of a reasonable person.

linking financial and non-financial materiality

The guidelines on materiality for non-financial reporting are modelled around the definitions of materiality for financial information by describing it in terms relevant to decision-making. As such, this puts it in the context of other information, assessing its qualitative and quantitative importance with respect to this other information and decision-making. However, there is a difference in the context of emphasis on the audience. Prominence is given to the users of non-financial information as this information impacts multiple stakeholders and not only shareholders.

There are multiple bodies that provide guidance on non-financial materiality, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and a few other non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Materiality is one of the Guiding Principles of the International Integrated Reporting Framework (IIRF). Although they do not provide a definition, it suggests that the company should define materiality in terms of “matters that substantively affect the organisation’s ability to create value over the short, medium, and long term” (Eccles et al., 2014).

The IIRC provides a materiality determination process for the purpose of preparing and presenting an integrated report, as follows:

- Identifying relevant matters based on their ability to affect value creation.

- Evaluating the importance of relevant matters in terms of their known or potential effect on value creation.

- Prioritising the matters based on their relative importance.

- Determining the information to disclose about material matters.

Considering all stakeholders in determining materiality

The judgement of materiality ultimately lies with the Board of Directors, and it forms the basis for establishing the legitimacy of the corporation’s role in society (Eccles and Youmans, 2015). There prevails an ideology across the globe that Directors’ fiduciary duty lies primarily to shareholders. However, shareholders are just one stakeholder that makes a corporation successfully function. On the contrary, there are other providers of financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, and natural capital who have an interest in the organisation.

Future generations are also stakeholders in the continued success of the business. Considering the interests of all stakeholders and taking into account multiple time periods, the fiduciary task of Directors’ seems impossible as corporations have limited resources. Therefore, this brings in the need to determine which stakeholders and issues are significant and, thereby, material. Eccles and Youmans (2015) suggest that directors should focus on significant audiences, and this implies a broader range of issues over a longer time frame to consider in determining materiality.

moving forward

Organisations can use material information to align their sustainability strategies with their business goals. When organisations understand the sustainability issues most relevant to their operations, they can integrate sustainability into their core strategies, drive innovation, and improve long-term performance. As a result, this enables them to contribute positively to all stakeholders and focus on enhancing their sustainability goals (Apraava Energy, 2022).

A benefit to corporations (specifically) of material sustainable reporting is risk management. In essence, identifying and addressing material ESG risks is vital for sustainable business practices (Gorley, 2022). Materiality assessment allows organisations to understand and manage potential risks associated with environmental and social impacts, governance failures, and regulatory compliance. By addressing these risks proactively, organisations can reduce their exposure to legal, reputational, operational, and financial risks.

Why is it essential to focus on Sustainability materiality?

There are several key reasons why materiality is important in sustainability reporting. Firstly, it helps organisations focus on the most relevant issues faced in their operation, the industry, as well as their stakeholders. By concentrating on these issues, organisations can allocate their resources effectively and address the most pressing concerns (Jørgensen et al., 2021).

In addition to relevant information, materiality assessment also ensures that sustainability reports provide accurate and concise data (Petrescu et al., 2020). By focusing on material issues, organisations can avoid reporting overload and information fatigue (Edmunds and Morris, 2000). This allows stakeholders to access meaningful data that supports their decision-making processes. That is, as long as organisations commit to transparency and accountability.

Thirdly, materiality helps businesses to engage with stakeholders more effectively, including investors, customers, employees, communities, and regulators. By reporting on material environmental and social issues, organisations can thus provide transparent and reliable information that meets stakeholder expectations. This enhances trust, improves relationships, and fosters a two-way dialogue between organisations and their stakeholders (Apraava Energy, 2022).

Overall, materiality in sustainability reporting helps organisations prioritise their resources, engage stakeholders, manage risks, align strategies, and provide relevant information. Materiality is one of the 12 key pillars of the Systems Holistic Model for thrivable transformations and strong sustainability (Fedeli and Shrestha, 2020). By incorporating materiality into their reporting practices, organisations can enhance their sustainability performance. In turn, organisations can drive innovative and positive change, further contributing to a more sustainable future.

Achieving the United Nations Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs) and how they link to materiality

Materiality plays a crucial role in achieving the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs are a set of 17 global goals aimed at addressing various social, economic, and environmental challenges by 2030. Materiality helps organisations focus their efforts and resources on the areas where they can have the greatest impact.

The SDGs cover a wide range of issues, from poverty and inequality to climate change and environmental conservation. Materiality helps organisations identify which specific goals and targets are most relevant to their operations and stakeholders. This allows them to prioritise and allocate resources effectively.

Materiality assessments enable organisations to align their business strategies with the relevant SDGs. By identifying key areas of impact, organisations can develop targeted action plans that contribute directly to achieving specific goals. Further, addressing material issues related to the SDGs can help organisations mitigate potential risks. For example, by addressing supply chain sustainability or community engagement, companies can reduce the likelihood of disruptions, reputational damage, or legal issues.

A Thrivable Framework

Many organisations use aspects of THRIVE’s 12 Foundational Focus Factors (FFFs) in addressing sustainability challenges. These aspects form the Systemic Holistic Model are divided into Four Quadrants: ‘Significance’, ‘Scale’, ‘Scope’ and ‘Shift’. Materiality is one of the FFFs that fall under the quadrant of ‘Significance’. Significance considers what is material across all capitals and measures it in an integrated way.

‘Significance’ considers and assesses the relevance and interdependencies of different types of resources. It’s not only in relation to financial capital but also manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural capital. Significance considers why we need to address these concerns and what the impacts are if we don’t. It separates a weak sustainability strategy from a strong one.

As we strive to thrive, humanity and the environment must co-exist beyond merely being sustainable. An expansive approach that integrates all perspectives together and acts in unison is necessary to measure sustainability and guide towards thrivability. The Systemic Holistic Model allows for a more consistent appraisal of sustainability performance. It’s also a tangibly productive template for holistically evaluating the systemic interactions of industry and operations and their impact on society and our global environment.

The THRIVE Project is researching, educating and advocating for a future beyond sustainability. To learn more, visit our website. You can follow our informative blog, podcast series, and live webinars featuring expert guests in the field. Sign up for our newsletter for regular updates.